Welcome back to RENDERED!

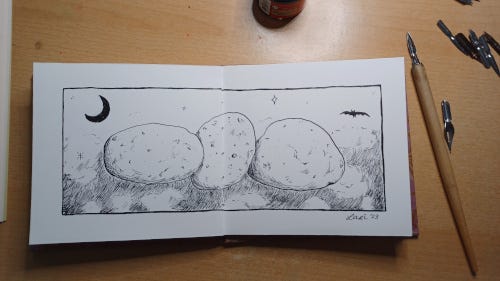

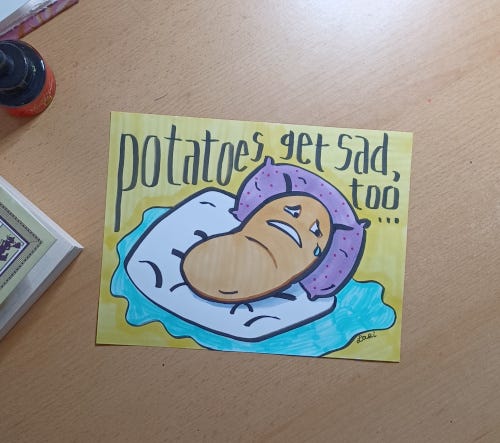

Fun fact: Did you know that Substack offers an AI-generated art feature? Here on RENDERED, there is no place for that nonsense. RENDERED is written, researched and illustrated by me, so if you enjoy my work, please support this indie artist.

More on that later. For now, on to this month’s essay!

We’ve turned our clocks back, the cold rains have begun again, and potatoes are back on the menu in full force. Tartiflettes and potato pancakes, oven-roasted wedges, mashed atop a parmentier, I’ll take ‘em all.

I’ve got a penchant for potatoes. They are my love language. Serve me an undercooked potato, and you risk breaking my heart. Seriously, I will take it personally.

My husband knows I don’t play around with potatoes, so when he served me up a portion of the first cheezy, creamy tartiflette of the season, it sent me to my Happy Place. And with a belly full of warm spuds, I unknowingly flipped open a book and read the passage that would inspire this essay.

From New England Legends & Folklore:

“... [S]o long as the twin mysteries of life and death confront us with their unsolved problems, it is certain that where reason cannot pass beyond, the imagination will still strive to penetrate within, the barrier separating us from the invisible world. This invisible world is the realm of the supernatural. [...] I have myself known intelligent men who were in the habit of carrying a potato, [...] as a cure for the rheumatism.”

Wards, talismans and charms are valued across different cultures–but I’d never heard of a potato falling into that category.

What’s so special about potatoes? Why the air of mystery and superstition?

The oldest wild potato specimen (Solanum maglia) was found at a prehistoric archaeological site in Chile–potato skins in a bowl date back to about 13,000 years ago. Potatoes were (and are) not only a foodstuff, but also a part of indigenous mythology.

When the Spanish conquistadores arrived in Peru, writings referred to this new food as papa (the original name), or turmas de tierra (earth truffles). Once transported to Spain via the Canary Islands in the 1550’s, the name became patata, because “papa” in Spanish refers to the Pope. Potatoes were then brought to Ireland and Britain sometime in the 1590’s.

It took time for potatoes to catch on in Europe… they reminded people of truffles at first, which were not the luxury item we know today. Truffles, those devil mushrooms, had an uglier reputation in medieval European superstition, considered to be linked with evil and death, as their growth was associated with lunar cycles and witchcraft.

Those potatoes were also small, watery and bitter-tasting, which made them unappealing compared to other tubers from the Americas like Jerusalem artichokes and sweet potatoes.

Thus, potatoes were initially seen as a food fit only for pigs and convicts.

Skepticism about the unfamiliar potato also birthed superstitious beliefs: Some even believed potatoes could carry leprosy, and even spread the bubonic plague.

It took convincing for people to catch on to potatoes in France. Hachis parmentier (cottage pie) takes its name from Auguste-Antoine Parmentier, an army officer who was imprisoned during the Seven Years War, during which time he ate a ton of potatoes and realized… hey, these ground nuggets ain’t so bad! He wrote in 1772 that potatoes were, in fact, safe to eat, and they could provide necessary sustenance to those who were starving under the grain scarcity and food shortages. (Read more about food shortages leading up to the French Revolution in my essay on the history of baguettes.)

Parmentier convinced King Louis XVI of the promise of potatoes, and apparently even Marie Antoinette started wearing potato flowers as adornment. In 1775, Parmentier received permission from the King to manufacture public interest in potatoes. He ordered that fields outside of Paris be planted full of them, and kept them patrolled under armed guard by day… but unprotected by night. People grew intrigued, and snuck onto the fields to steal potatoes at night. Whatever it is, it must be valuable if it’s kept under guard, right?

The power of suggestion being what it is, potatoes (or “the poor man’s bread”) began to spread throughout the Parisian region, and finally across France.

Potatoes became a staple food among the indigent tenant farmers of Ireland, who had precious little land to grow their own food, all while they harvested grain for the English. Leading up to 1845, the Irish began to rely on cultivating only one potato variety to feed the country’s growing population. However, this variety was vulnerable to a potato blight (a type of fungus), which hit in the 1840’s. This led to mass crop failures, and between 1845-1849, the Great Famine ravaged the population of Ireland.

All the while, huge quantities of grain continued to be exported from Ireland into England; wheat, oats, and barley were “money crops,” not “food crops.” The British government, under military guard, transported tons of food out of Ireland during the worst years of the famine.

***

The nature of superstitions is varied–sometimes both a belief and its inverse exist simultaneously. One potato superstition promises that a potato in the pocket will cure rheumatism, and another guarantees to keep it away altogether.

These potato superstitions date back to Victorian days in England and the United States: this was before medicine could effectively treat rheumatism, and folk remedies were all common people could rely on for relief. In fact, there is actually a collection of magical potatoes collected during that time, kept at the Pitt Rivers Museum at the University of Oxford in England.

It isn’t important that superstitions are illogical, but that they are mysterious; believing in an invisible promise inspires satisfaction.

An excerpt from a 1907 academic text “Superstition and Education” claims that men were more prone to belief in superstitions than women when facing tough times.

“[...] [H]istory makes it very plain to us, that when men become excited and wrought up in their emotional natures, they are guided far more by emotional and superstitious reactions than by reason.”

Advertisements for clairvoyant services, tarot readers and fortune tellers, and occult guidance were prevalent at the time.

This was the tail-end of the spiritualism movement that picked up especially among monied circles in the post-bellum United States, reaching its peak around the turn of the 20th century.

In those post-Civil War years, there was increased interest in communing with the spirits of the deceased via séances, in order to cope with the sense of loss. Even First Lady Mary Lincoln practiced spiritualism in the White House, following the death of her son Willie in 1862.

During the Civil War, many souls were lost, and could not be laid to rest by their bereaved families–even getting information about their missing loved ones often proved impossible. After the horrors of the war, a generation in mourning was in need of comfort and closure that traditional religion could not offer.

***

“Superstitious” has a ring of disparagement, doesn’t it? Calling someone superstitious is another way to trivialize, even denigrate, them as illogical. That their misguided intuition indicates a lack of rationality.

But “Superstitions are a bunch of hooey” is as daring and revelatory as declaring that WWE wrestling is staged.

Both require a collective agreement to engage in the suspension of disbelief. While superstitions are not based in hard-and-fast science, they still carry cultural weight, and can even provide psychological and emotional benefits: calming a sense of anxiety, or providing comfort in a vulnerable situation outside of one’s control.

Potatoes and rheumatism aside, there are so many superstitions around food and well-being: eating certain foods at New Year will bring prosperity; garlic will ward off the evil eye; if you make a wish before blowing out your birthday candles, it will come true…

As my folklore book reminds me, beyond the limits of reason lives the imagination. If, within that imagination, there exists a way to ward oneself against harm and misfortune, then what’s wrong with that?

Thank you for reading! I’ll be back later this month with a new TIDBITS narrated essay for paid subscribers, and then in December with a new RENDERED essay for everyone.

News from the studio:

ART COMMISSIONS: I am available for commission! Holiday season commission requests are still possible, inquire via my website.

WEB SHOP: New items will drop on November 15th! Cyanotypes, water marbled cookbook pages, mystery packs, and more.

INSTAGRAM: I am most active on Instagram, so follow me there to stay up-to-date with my world.

RENDERED is a one-woman production, and your support is appreciated! If you're hungry for more content in audio format, consider a paid subscription. ALL paid subscriptions (5€/month, 40€/year) are entitled to a copy of my zine, “The Best of RENDERED, Vol. 1” while supplies last. Hand-bound, printed locally here in Anjou, France on recycled paper. All paid subscribers also have access to TIDBITS narrated essays and a permanent discount in my web shop. Art Collector subscribers (65€/year) receive a custom piece of art in addition to the above perks.

Bibliography

Davidson, Alan and Tom Jaine, ed. The Oxford Companion to Food, Third Edition. Oxford University Press, 2014. P. 418, 645-6.

Drake, Samuel Adams. “New England Legends & Folklore.” Chartwell Books, 2017. p. Vi-vii.

Dresslar, Fletcher B. “Superstition and Education.“ Berkeley: University Press, 1907. p. 4, https://www.loc.gov/resource/gdcmassbookdig.superstitioneduc00dres/?sp=12&st=text&r=0.13,0.66,0.753,0.785,0 214.

Rhodes, Ella and Alex Fradera. “The Everyday Magic of Superstition.” The British Psychological Society, 12 Oct 2016. https://www.bps.org.uk/psychologist/everyday-magic-superstition

Kommel, Alexandra. “Séances in the Red Room: How Spiritualism Comforted the Nation During and After the Civil War.” The White House Historical Association, 24 Apr 2019. https://www.whitehousehistory.org/seances-in-the-red-room

“Learn About the Great Hunger.” Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum, Quinnipiac University. https://www.ighm.org/learn.html

Ropert, Pierre. “Petite histoire de la pomme de terre, objet de culte, de superstitions et de convoitise.” France Culture, 11 Dec 2018. https://www.radiofrance.fr/franceculture/petite-histoire-de-la-pomme-de-terre-objet-de-culte-de-superstitions-et-de-convoitise-3426120

Spooner, David, et al. “The Enigma of Solatium Maglia in the Origin of the Chilean Cultivated Potato, Solarium Tuberosum Chilotanum Group.” Economic Botany, vol. 66, no. 1, 2012, pp. 12–21. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41493896.

Yummy! The mention of salt and butter made me get dreamy....