Hello, and welcome back to RENDERED. This essay required some extra simmer time, and so I thank you for your patience. Stay tuned until the end for an announcement.

Every year, winter is butter season. Butter is not a year-round ingredient in my kitchen. It's not until the days shorten, bringing the damp chill that makes my stomach quiver, that I desire the unctuous warmth of butter. And when butter season does arrive, I use it in dishes that benefit from its richness. Let it sing, give it the respect it deserves.

Onions, translucent;

mashed potatoes, luscious;

chocolate chip cookies, decadent;

garlic and spices, fragrant;

sautéed potatoes, richly browned;

croque monsieur, cheezy...

I'll take it all!

If you know me IRL, it's no secret that I hate the winters here. It's cold and wet and windy and miserable. That traitorous bastard The Sun goes on hiatus for 6 months, and everything is dishwater gray and dingy. Harsh rain stings my face, and the sharp wind cutting off the rivers makes an umbrella utterly useless. The days are half as long as in the summer, so my instinct tells me to burrow into my sofa, and keep my belly full and my toes warm until spring.

The season dictates that which my constitution craves. Like any life cycle, it feels like the natural order of things.

But the relationship to seasonality goes far beyond food. The diet not only changes, but other needs change. Clothing, food, sleep, time spent outdoors, comfort. In the winter, I need more comfort, more warmth, more rest than the rest of the year.

The larger culture urges us to purchase our seasonal indulgences, all that annoying encouragement to lean into the "seasonality" of buying habits. (I mean, come on... "Black Friday" sales in France?) Online, all around the city, in our eye holes and our ear holes.

What exactly is butter? When cream (36-44% fat) is agitated, the globules of fat present in the liquid are damaged, releasing liquid (buttermilk). The fat globules are now free to clump together, gradually until they become one large mass of fresh butter. It is separated from the liquid, which by now is about 0.5% fat. The buttermilk may be lightly fermented (cultured), or not (sweet), and used in other preparations.

The richer the milk is in carotene pigments (from well-pastured animals), the richer in color the resulting butter will be. Nowadays, some manufacturers add achiote (annatto) to bump up the color intensity. (I previously wrote about this ingredient in RENDERED 9: Annatto)

When butter is heated up, the milk solids brown and provide a nutty flavor. Remove the milk solids and you've got clarified butter. To make ghee, butter is made from soured milk, then heated to brown the milk solids, and finally strained. Smen is made from salted fresh butter, which is fermented until it takes on a much stronger flavor. Niter kibbeh is a fragrant East African (Ethiopian, Eritrean) clarified butter that is flavored by simmering with spices.

The history of butter seems quite straightforward (domesticated animals = milk = butter), but my question while researching was: how did it become a worldwide product?

If you want butter, of course you need lactating animals nearby that trust you enough to get near enough to milk them. So to find the origin of butter, we have to look back at humanity's early relationship with animals.

Sheep and goats were domesticated in the Fertile Crescent, between 8000 and 9000 BCE. Cattle would join the party about a thousand years later. The next millennium, dairying would spread through to the Mediterranean. Clay sieves in northern Europe, which indicate the practice of dairying, date back to 5000 BCE.

Saharan rock drawings of milking appear about a thousand years later. Keep in mind: this was during the African Humid Period, or Green Sahara--during this time, the Sahara was chock-full of vegetation, straight across to the Arabian Peninsula. The African Humid Period ended about 5,000 years ago and the region's climate changed again, increasing desert conditions which pushed more people toward the Nile River. Later, we see proof of cheesemaking appears in Egypt in 2300 BCE.

Before European colonization began, milk consumption (and presumably, milk products including butter) was mostly relegated to Eastern and Northern Europe, sub-Saharan Africa, the Indian subcontinent, and Central Asia.

Milk from cattle, sheep, goats, water buffalo, yaks, and even camels can be used for butter. Once it's been collected, fresh milk will naturally separate if it's left to stand--the cream rises to the top, which creates butter when agitated. The remaining milk can be fermented to make yogurt, or salted to make fresh cheese. Milk spoils quickly if it isn't used right away, so dairying provides a decent preservation technique.

Archaeologists have found "bog butter" in the highlands of Scotland and Ireland. Wrapped in bundles or in buckets, hunks of fresh butter were buried in bogs to preserve it, and potentially serve as a spiritual offering. The earliest proof of bog butter dates back to the Iron Age (400 BCE).

These pots of bog butter are from a time when transhumance (seasonal migration of people and livestock) was a traditional practice. In the summertime, the cows would be taken up to the highlands to graze, while the lowlands were used for other agricultural purposes. Without refrigeration, milk and its byproducts don't last long--so freshly-made butter would be wrapped and placed into baskets, then placed into the bogs in order to keep fresh. This pastoral tradition is noted as late as the early 1900s in Ireland, and the ancient origins of this practice are clearly illustrated with artefacts.

Did you know the majority of humankind is lactose intolerant? Estimates I found ranged between 68% - 75%. A genetic mutation in European peoples increased during the Neolithic period--this mutation is responsible for the production of the lactase enzyme, which allows lactose sugars to digest. This corresponds with a change in diet of Neolithic humans in Europe, through the 4th millennium BCE.

The Greeks and Romans preferred olive oil for culinary preparations, using butter primarily as an ointment. Fast forward to medieval times in northern Europe, and butter was considered a food for peasants. But after the 15th century, when the Catholic Church decreed it was permitted for Lent, Europeans more widely developed a taste for it.

However, in places like the Americas, where cows were not native species, things looked different. Milk and its byproducts were not a typical part of Indigenous diets.

Across North America, Indigenous peoples hunted animals like bison, elk, bears, and deer... but those animals were left to roam naturally. By using fire to strategically cull underbrush and extend grassland conditions, a natural corridor was maintained to encourage and entice those herd animals along their migration route. There was not the same system of mass domestication as seen in Europe, but rather a way to lure animals in where they could be hunted. It wasn't necessary to pen them in, nor to claim them as property. These concepts around animal treatment were imported by Europeans, imposed with deadly force.

Native animal species that were domesticated were neither equipped nor raised to produce much milk. Llamas and alpacas were domesticated (and selectively bred) in pre-Incan Andean cultures more than 6000 years ago. Beasts of burden, they also provided transport, leather, meat and wool--but very little milk.

In the 15th century, domestication of herd animals was commonplace in Europe--meat was, for them, a necessity that had to come along for the ride. So, European colonizers (French, English, Spanish, Dutch) brought animals like cows, pigs, and sheep to the Americas, Australia and beyond.

The Spanish encouraged the reduction of alpaca and llama in favor of cattle and sheep from Europe--for meat and wool, and to deprive local people of their means of sustenance. On top of it, the Spanish circulated rumors that alpacas carried syphilis, which only helped to encourage breeding the newly-arrived cattle.

Consistent access to dairy products like milk, yogurt, butter and cheese requires a stable population of animals that allow you to get close enough to milk them regularly. Wild animals aren't so keen on letting humans close enough to fondle their undercarriages.

Control over their breeding is also essential: you can only have consistent access to milk if you know exactly when and which animals are pregnant or have given birth.

These conditions are met when you declare the animals your private property. In Virginia, it was established in 1623 that the penalty for stealing an animal (considered the Crown's property) worth over 12 pence was death. Those animals provided not only the meat and milk that Europeans were accustomed to, but also a strong social significance--property, wealth, access, power. More livestock, more land and resources necessary, more profit to be generated.

This profit-driven mindset is typical of imperialism, which prioritizes above all the extraction of resources from people, natural ecosystems, and animals.

This is animal colonialism: the European use of animals as an invasion tactic (destruction and replacement of native fauna species to feed and reinforce their foreign dietary norms, imposition of the foreign idea of legal status, justification of expansion and seizing of resources to that end). Importing herds of animals disrupted/upset the local ecosystems already in place, suppressing the ability of Native peoples to survive on their land. This is the backdrop for part of the reasoning why eschewing dairy is a way of decolonizing the diet.

Seasonality: The same way we change how we dress for the weather, how late we stay up, how much time we spend outside, how much we desire certain foods, it fluctuates.

Just when I arrived in butter season this year, the seasons changed, the days grew shorter, and I realized that I had set myself up. I had forgotten to rearrange things, to account for that natural change in pace.

As a self-employed person, I've found that I have committed to imposing upon myself the desire to overwork. But this is a habit I developed over my entire work career: the way institutions demand that every minute be productive and accounted for. Rush, work long days, push on mechanically, run yourself into the ground. Progress must be quantifiable, and is insensitive to our natural fluctuations. The body must be used to generate profit.

It seems to me that seasonality and rest are complementary.

Rest is the refusal to participate in the mindset of endless pursuit of profit, and the use of one's body as commodity. There is power in dictating when and how one rests. The ability to get quality rest has historically been outside the reach of people in marginalized communities--those from whom labor has been extracted for generations.

Tricia Hersey, founder of The Nap Ministry and author of Rest is Resistance, asks us to imagine: What if we considered rest as a necessity for all rather than a luxury for a few? She advocates for reimagining rest and collective care as a way to resist oppressive (white supremacist/capitalist/patriarchal) systems and pursue bodily liberation.

While I was writing this essay, I had to re-examine some of this essay's ideas in the context of my own world. This is why I've decided to change my RENDERED writing schedule. I've spent 2022 divided between multiple endeavors including this newsletter, and I realized it's time to start slowing down.

Moving forward, there will be one issue per month, alternating between RENDERED (illustrated essays, free for all) and TIDBITS (bonus narrated essays and bonus content, for paid subscribers).

I've put many hours of emotion into this newsletter, my creative outlet which has become part of my livelihood. January 2023 makes 2 years of RENDERED, and moving forward, I wish to slow down and simmer each essay a little longer.

Thank you for your readership. If you're interested in supporting my work, consider a paid subscription (there's a *new* subscription perk, read below), visit my web shop (where I now offer prints), commission some original art, or just share RENDERED with a friend!

Have a safe holiday season. See you in 2023.

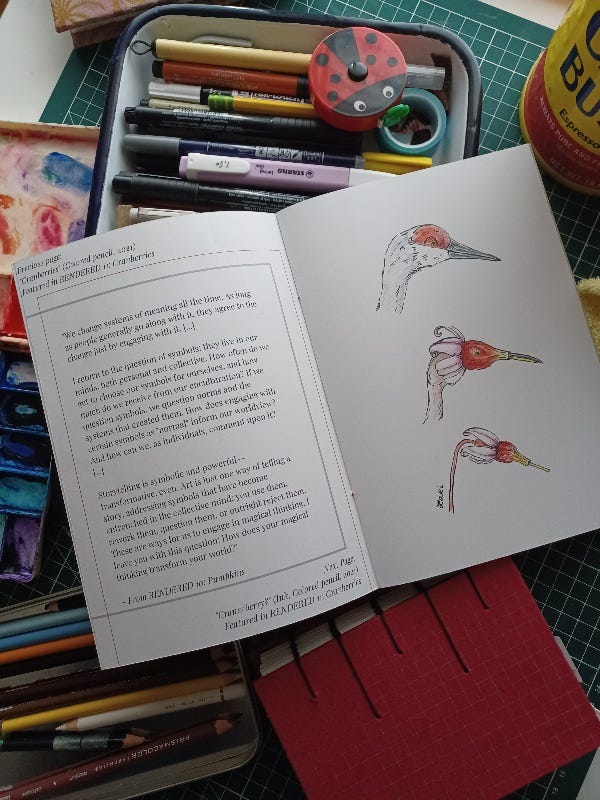

I'm proud to reveal one of my behind-the-scenes projects, my very own zine: "The Best of RENDERED, Part I." Printed locally on recycled paper, and hand-bound by me, the zine includes 10 illustrations (1 never-before-seen), and selected essay excerpts. Designed by yours truly, you can easily undo the binding, cut it up and display the illustrations. This is a *new perk* for Yearly paid subscribers.

Monthly subscriptions (5€/month) receive:

* Access to the full archive, including bonus TIDBITS narrated essays

* Discount codes in my webstore

Yearly subscriptions (40€/year) receive everything above, plus:

* "The Best of RENDERED, Part I" zine (while supplies last)

* RENDERED logo sticker (while supplies last)

Art Collectors (65€/year) receive everything above, plus:

* Custom-made painting (A6/postcard-size)

Subscriptions may be gifted--you can get these perks yourself, or you can gift them to someone special.

If you're a current Yearly Subscriber, you may e-mail me (lari@larisanjou.com) with shipping details to receive your zine and sticker. It's a retroactive bonus perk and a thank-you for your support.

Bibliography

"Choreography of the Body’s Collapse: The Anti-Capitalist Politics of Rest." InVisible Culture: An Electronic Journal for Visual Culture. Dialogues, Issue 32. 25 Apr 2021.

Cohen, Mathilde. “ANIMAL COLONIALISM: THE CASE OF MILK.” AJIL Unbound, vol. 111, 2017, pp. 267–71. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/27003743. Accessed 17 Dec. 2022.

Costello, Eugene. "The Lost Art of 'Booleying' in Ireland." Raidió Teilifís Éireann, 31 Aug 2021.

Davidson, Alan. Tom Jaine, ed. The Oxford Companion to Food. 3rd Ed. Oxford University Press, 2014. p. 121-22.

Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. An Indigenous People's History of the United States. Beacon Press, 2014. p. 27-9.

Earwood, Caroline. “Bog Butter: A Two Thousand Year History.” The Journal of Irish Archaeology, vol. 8, 1997, pp. 25–42. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/30001649. Accessed 12 Dec. 2022.

"Food Seasonality." First Nations Development Institute, 2015.

Helmer D. & Vigne J.-D. 2007. "Was milk a “secondary product” in the Old World Neolithisation process? Its role in the domestication of cattle, sheep and goats." Anthropozoologica 42 (2): 9-40

Keoke, Emory Dean and Kay Marie Porterfield. Encyclopedia of American Indian Contributions to the World. Checkmark Books, 2003. p. 2, 10, 133-34, 158.

Jankowski, Nicole. "Spread The Word: Butter Has An Epic Backstory." NPR's The Salt, 24 February 2017.

McGee, Harold. On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. Scribner, 2004. p. 10-11, 32-37, 50.

Paloma Diaz-Maroto, Paloma et al. "Ancient DNA reveals the lost domestication history of South American camelids in Northern Chile and across the Andes." eLife. 2021; 10: e63390. Published online 2021 Mar 16. doi: 10.7554/eLife.63390

Schmidt, Alex. "Smen Is Morocco's Funky Fermented Butter That Lasts For Years." NPR, 9 Oct 2014.

Sherman, Sean. "This Healthy Diet Has Stood the Test of Time." Bon Appétit, 18 Oct 2017.

"Tricia Hersey: Rest & Collective Care as Tools for Liberation." Youtube, Uploaded by Sounds True. 9 Apr 2021.

"When the Sahara Was Green." Youtube, Uploaded by PBS Eons. 10 Mar 2020.

Butter....and a nap! Exquisite!