Happy New Year, and welcome back to RENDERED. This month's issue is a bit late, but circumstances being as they are, I hope you'll indulge me. I've been spending time with my family, while dealing with coronavirus-related delays that have kept me away from my studio. In short, I needed a break.

This essay is Part I, as the subject of rice cakes is so vast. Part II will be released on February 1st, in the form of a narrated essay, as part of my TIDBITS series, available to paid subscribers.

Thank you for your patience, and now: let's get into it!

Rice cakes are a food of tradition, often associated with the New Year festivities, a time to come together and enjoy connection: with each other and with a larger culture, bolstered by inherited foodways. I start this tour of rice cakes ahead of the Lunar New Year, with a focus on mochi (Japanese rice cakes), and my own history with them.

When you think "rice cakes," you might be thinking of those styrofoam-esque puffed rounds sold in plastic sleeves in the diet aisle. It's a shame they share the same name as pounded rice cakes, because they are two very different foods. When searching "origin of puffed rice,” you'll find it's attributed to botanist Alexander Anderson, who was playing around with starch crystals in his laboratory, and found that they would "puff" when heated under pressure. He created a pressurized machine (or "cannon") that popped out puffed rice, attracting investors, and eventually demonstrating his rice-puffing cannon invention at the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair. Enthusiastic onlookers bought about 250,000 bags of the stuff, at a nickel a pop. Quaker Oats took notice and was quick to start marketing the puffed rice.

Some sources say this guy Anderson "discovered" puffed rice, but it's more like he stumbled upon a food that had already enjoyed a long history in places like southern India.

The New Year: for many, it means reflecting on the last year, taking stock of where you've been, what you've gotten up to, the highs and lows, the goals that went unrealized, those that were accomplished. I'm not one for New Year's resolutions per se, but I do clean my house and burn incense to cleanse my home of the old year, and refresh the energy for the New Year. I think about my values, and where I'm putting my energy: is my life in alignment with my core values? Am I prioritizing my well-being? Do I feel like I'm going in the right direction?

2021 was when I chose to leave my day job, in the interest of prioritizing my mental well-being and core values. I also chose to spend a large chunk of time in the United States with my family. (Oh, how I missed New England winters... the cozy warmth of the midday sun, looking out a frosty window at the brilliant diamond snow...)

Recently during my time back in the US, I was up one early morn before the crack of dawn. Jetlagged in my mom's living room, flipping TV channels, a snippet of a familiar song started playing--"Progress" by Kokua. (Listen on Youtube here.)

I lingered--not having heard it in years, not having thought about it for years. It was a nostalgic glint back to a warm, soothing feeling of hope and ambition, desire for excellence and happiness and a world full of realized dreams.

The song brought me back to my student days in Japan. I'd go to music shops in hip neighborhoods in Osaka, buying random cheap used CD's that had cool cover art. Some were duds, others were pleasant surprises, and a few were absolute bangers. (I was able to score a lightly dogeared first-edition copy of the Merveilles album by Malice Mizer, an album I still listen to with remnants of that teenage zeal. Listen to the album here.)

"Progress" by Kokua was one of the random singles I bought, not knowing it was a song especially made as the theme for "Professionals," an NHK television documentary series.

And here I was, pleasantly immersed once again in this song. With that heady old familiar feeling, I watched the episode: a profile on "Granny Mochi" Kuwata Misao, a 93-year-old woman who puts all her energies into creating delicious rice cakes (specifically, sasa-mochi). She grinds glutinous rice in a mill to get the flour; grows her own azuki beans to get the right sweet bean flavor; and takes her bike to bamboo fields to hand-pick the best leaves to wrap the rice cakes in. Decades of experience in making superb rice cakes. All this effort, to make excellent rice cakes so soft they melt in your mouth--she sells them at a local supermarket, where they sell out in minutes. (Watch the episode on Youtube here.)

According to Ms. Kuwata, she continues the labor-intensive practice to make her mochi because they bring joy to people. She got into her business by chance: after retiring from her career as a cook, she made mochi as a volunteer at a nursing home--her mochi were so delicious that it brought two women to tears. So, she decided to start a mochi business at the age of 75. Sparing no effort, she put her heart into those rice cakes that her mother taught her to make.

Rice has been cultivated for over 10,000 years. In Asia, this staple food has a diverse array of varieties. Glutinous rice, also known as sticky rice, is just one variety amongst many. Its high amylopectin levels mean the grain is more opaque when dry, and very sticky when cooked.

It has been cultivated for thousands of years in China and Southeast Asia, and there are many different uses for it, including for savory and sweet preparations, fermenting, and making rice cakes.

Its existence, its life story, is written into its genetic code. Phylogeography is the study of the connection between the geographic location and genetic diversity of a species.

The genetic mutation responsible for the low amylose seems to have sprung up from one source from which all other glutinous varieties originated. This research suggests that the origin of glutinous rice was in Southeast Asia, and it spread north and east subsequently.

It's a plant that has persisted over the years, and in turn, thanks to its unique texture, specific food traditions have developed. Glutinous rice dishes are particularly appreciated at festivals and holidays like New Year, throughout East and Southeast Asia. Some of these rice cake traditions persist despite attempts to suppress them (including during the Cultural Revolution in China and the Japanese occupation of Korea).

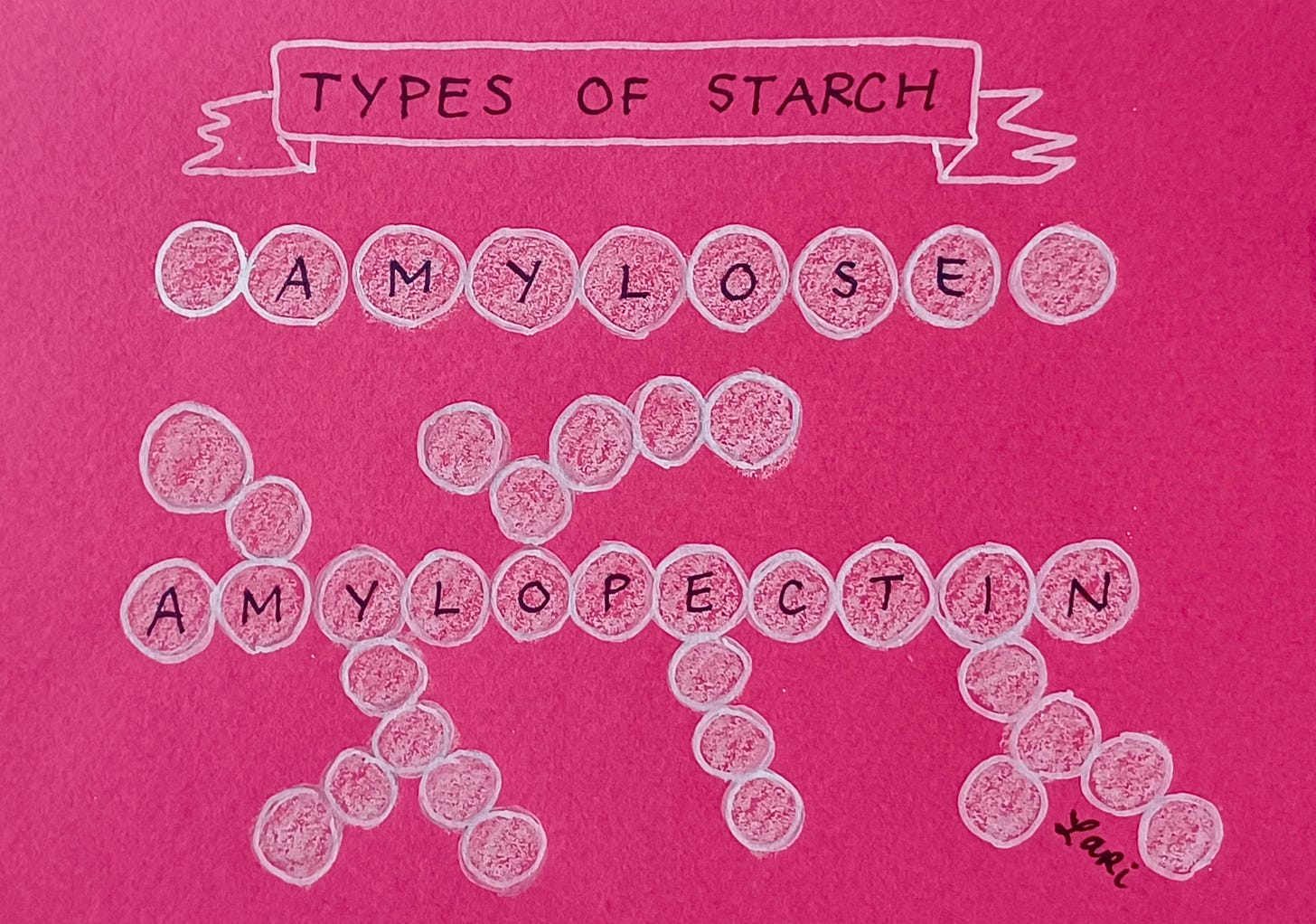

Mochi is a chewy, stretchy rice cake that can be flavored in many different ways. But: how does a grain of rice become rice cake? Rice cakes can be made either from pounding freshly-cooked glutinous rice, or by grinding the raw rice into a powder, then kneading together with hot water. Some rice cakes are also made by cooking the rice until it melds together, grains still intact, but cooked together into a sweet "cake" that can be cut into bars. There are 2 types of starch molecules: amylose (shorter, simpler chains of glucose sugars), and amylopectin (longer, more branched chains). Glutinous rice (or sweet/sticky rice) is almost pure amylopectin: when the rice is cooked, the starch molecules swell up. When the rice is pounded or kneaded, those complex chains of amylopectin mesh together, intertwining to form a durable, flexible mass: a chewy, smooth rice cake.

Rice has always been a staple of my diet, for personal and cultural reasons. But glutinous rice cakes? I was unfamiliar with them before going to Japan during college. I delighted in buying dango (flavored chewy rice balls on a skewer) and strawberry daifuku (mochi wrapped around a strawberry and sweet bean paste) as an afternoon treat. But much more than that, I learned that mochi is a food that has enjoyed a long history of significant tradition at the New Year.

Being in Japan gave me a strange feeling of hopeful joy and simultaneous anxiety. The wide-eyed optimism, and at times, shuddering naïveté. I was introduced to new levels of unfamiliarity and loneliness, a humbling experience. Especially during the holiday season.

I've written previously about finding "home" in moments of connectedness--home is an internal place, a link to something precious. I found that feeling in a warm family home in Kobe, making mochi with my friend and her mother on Christmas Eve 2007. I was touched they they opened their home to share this tradition and cook with me. At the New Year, my host family also included me in the festivities: eating toshikoshi soba on the 31st to say goodbye to the previous year; and ozoni soup with mochi on the first to greet the New Year. Visiting the local temple to pay our respects--the smell of incense as I waved it over my head, patting myself with the aromatic smoke.

At the heart of things, this food is my gateway to memories of connection with new people in a foreign place. Mochi represents the cozy certainty that lives in connectedness, ties to seasonal customs and familial food traditions. What a joy that I got to witness and share in it firsthand.

That New Year, I understood one of the guiding principles of my nature: In much of what I do, I gently seek connection.

If you enjoy munching on mochi, be careful: make sure to take small bites and chew thoroughly. These chewy rice cakes cause choking incidents every year, especially in children and the elderly. Really, it's a question of eating carefully, but I had to roll my eyes at the sensational headlines I found about mochi in Western media, like: "4 women choke to death on New Year's rice cakes as deadly trend continues in Japan." (As if eating mochi were a TikTok trend.) And this gem from the BBC: "Delicious but deadly mochi: The Japanese rice cakes that kill." Who knew that rice cakes could be so sinister? (I know, snappy headlines bring in readers, we're in an attention economy, blah blah...) Long story short, be careful when eating rice cakes.

Connection (and my search for it) occupies my imagination. I want to observe traditions that extend beyond myself, into a community. I want to create work that doesn't start and end with little ol' me. While I haven't yet made anyone cry with my food like Granny Mochi, I have myself been brought to tears while cooking, writing, listening to music, painting. In exploring those things which move me, I find it's a natural impulse to wish to share it.

Taking time off to be with my family, quitting my day job, cooking, painting, researching and writing this newsletter, and more: 2021 gave me opportunities to connect to my own values, my community, like-minded strangers, and my precious family.

Connection is at the heart and soul of RENDERED. It's a series of food stories that link history to art and personal experience, but also, to emotion.

Here's to more in 2022.

This is my 13th issue of RENDERED, marking one year of this newsletter. Thank you for reading, and for all your support. I look forward to bringing you more food stories and colorful illustrations. Be well, take care of your heart, and I'll see you next month.

Rice Cakes, Part II will be released as a narrated essay, or TIDBITS, available to paid subscribers this February 1st, which is Lunar New Year. I'll feature more information about ddeok (Korean rice cakes), and much more.

If you enjoy my work and would like to support my efforts, share with a friend/hit the "like"/leave a comment to help this newsletter grow, and consider a paid subscription for yourself or a friend. I also accept one-time donations via my website. To follow my art practice, follow me on Instagram or my website.

Bibliography

"Authorities urge elderly people to be careful when eating ‘mochi.’" Japan Today, 31 December 2021.

Golomb, Louis. “The Origin, Spread and Persistence of Glutinous Rice as a Staple Crop in Mainland Southeast Asia.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, vol. 7, no. 1, [Cambridge University Press, Department of History, National University of Singapore], 1976, pp. 1–15, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20070160.

Houck, Brenna. "The Rise and Fall of the Quaker Rice Cake, America’s One-Time Favorite Health Snack." Eater, 17 Sep 2020.

Johnson, Frederick L. "Anderson, Alexander P." MNopedia, modified 13 Oct 2015.

McGee, Harold. On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen, 2nd ed. Scribner, 2004. p. 457-9, 476, 804.

"'Mochi' Rice Cake: A Food for All Seasons." Nippon.com, 22 December 2018.

Olsen, Kenneth M, and Michael D Purugganan. “Molecular evidence on the origin and evolution of glutinous rice.” Genetics vol. 162,2 (2002): 941-50. doi:10.1093/genetics/162.2.941

"Rice." Britannica.com.

Swinnerton, Robbie. "Mochi: Power food packed with significance." NHK World-Japan, 11 Jan 2018.

"Through the Kitchen Window: Mochi Rice Cakes Wrapped in Bamboo Leaves [Misao Kuwata] - 15 Minutes." Youtube, uploaded by NHK World-Japan, 17 Sep 2020.

I learn so much from your newsletter. Happy one year to Rendered 🥳