Pasteles are, for myself and many others of Puerto Rican heritage, an indispensable part of the Christmas season. It is a food that takes ancestral know-how, and its ingredients echo the history of the island. Today, I explore this history of the tradition of pasteles de hoja, while asking: How do traditions travel with people, and how do they change along the way? What does it mean to be "at home"--in the kitchen, in one's family, and within oneself?

We've arrived at that time of year again: bombarded with lights, corny music, gift-giving adverts, all that Christmas season hoopla. I tend to avoid crowds (except to see the lights), make gifts for people I love, decorate my home and stay there. I'm not into the sappy Christmas music, except for a few classics... I admit I'm a sucker for Karen Carpenter's smooth fluttering crooning. ("Merry Christmas, Darling" always hits me in the feels.)

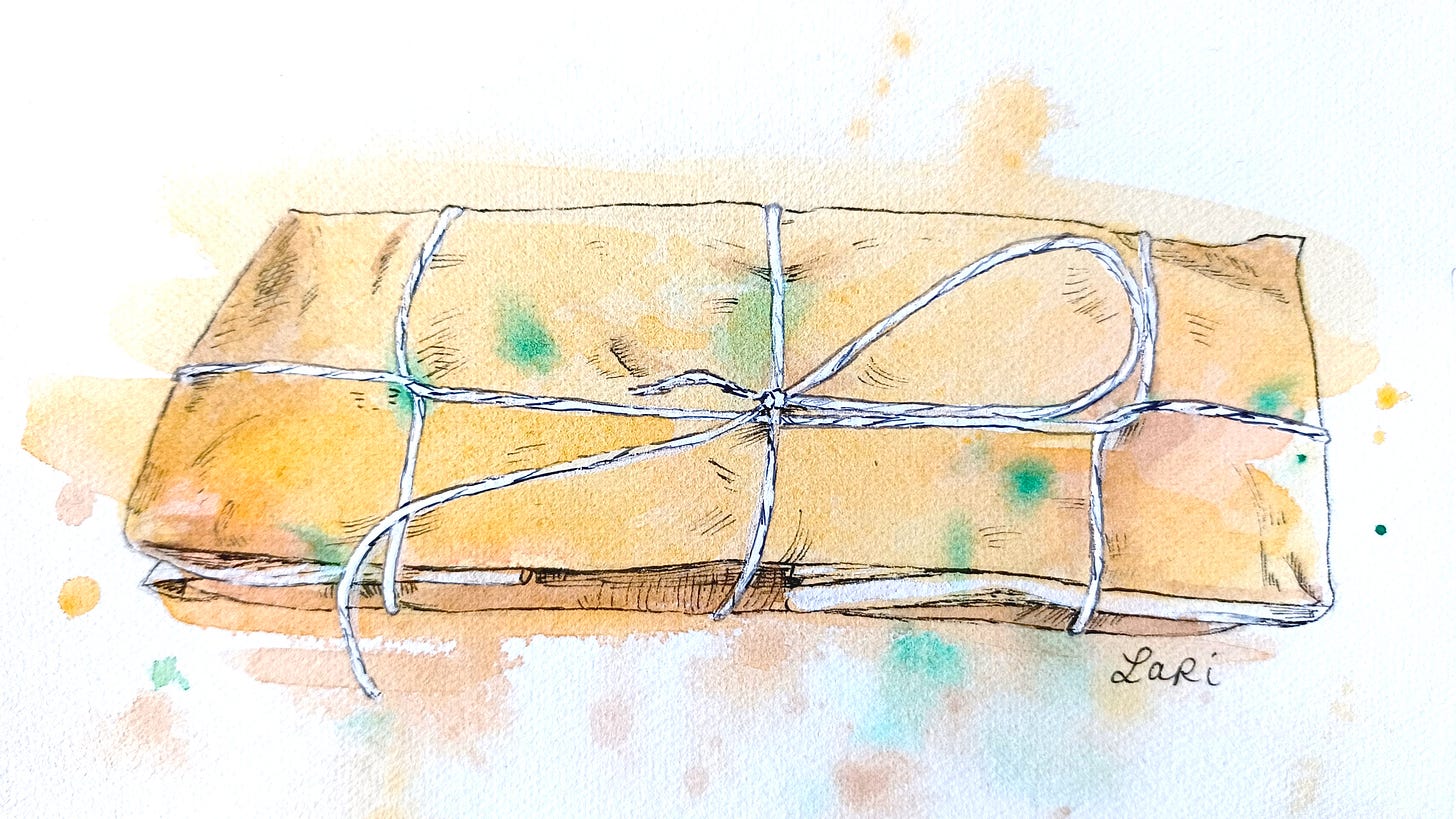

To me, the holiday season means it's time to make pasteles. Considering that I'm the only person of Puerto Rican heritage I know 'round these parts, logic dictates that if I am to have them, I must make them myself. (How very Vulcan of me.) Normally, making pasteles is a group activity: multiple hands make the immense amount of work more manageable. I do it all on my own, which means it takes 2 or 3 days of work: Day 1 is spent shopping at several stores for ingredients, and days 2/3 are for preparation, assembly, and cooking. All this is for about 2½ dozen pasteles, which my husband and I will savor during the holiday season.

You might be asking: Why even go through all the trouble? The cost, the time, the energy, for a relatively small amount of food that only 2 people will get to taste?

The short answer is: because this tradition makes me feel at home.

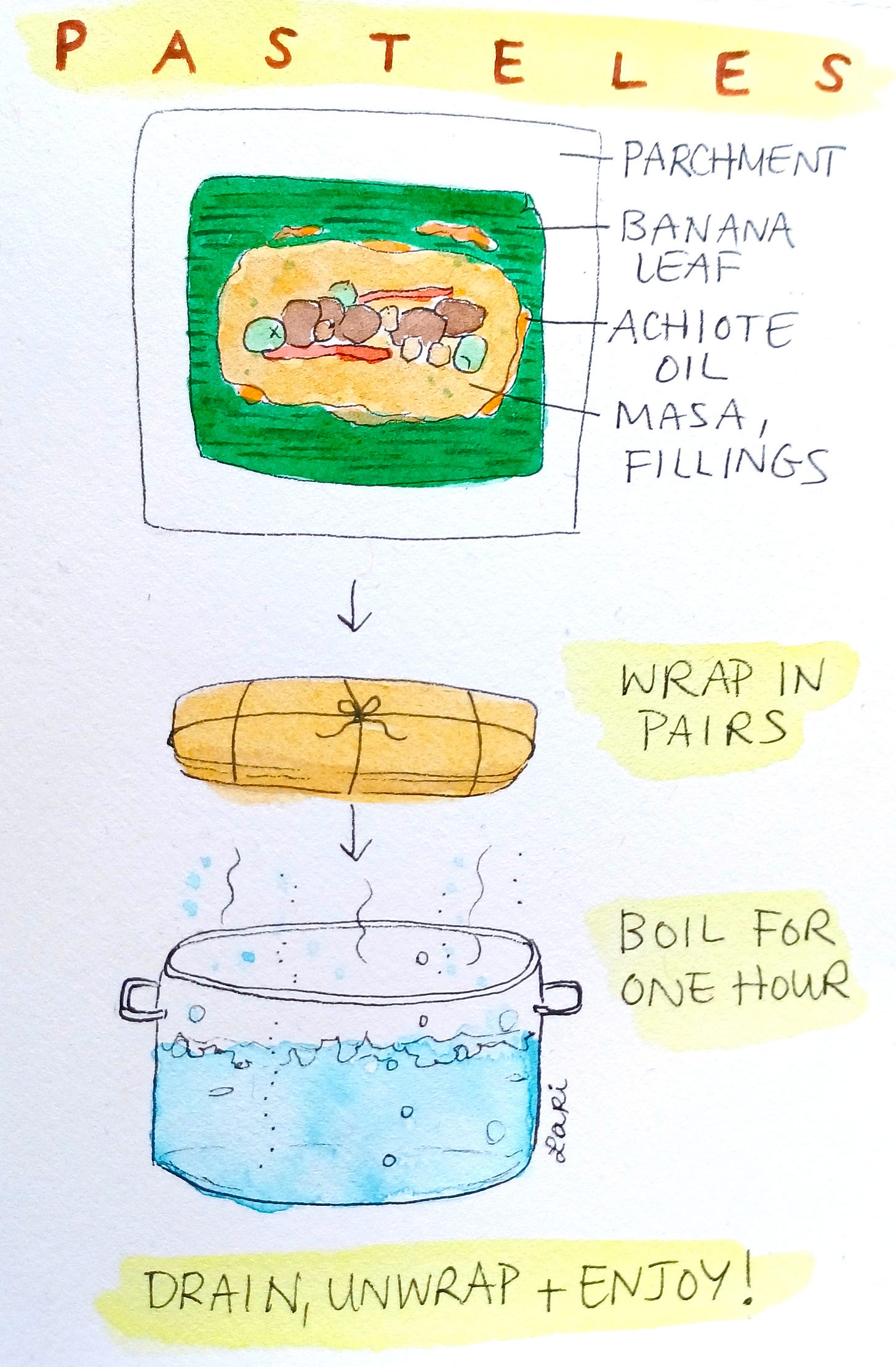

Puerto Rican pasteles are a dish that not only reflect the rich legacy of the history of the country, but also hold a special place in familial tradition. It consists of a paste of assorted root vegetables and green bananas or plantains, stuffed with fillings (not limited to: meat, garbanzo beans, hot or sweet chili peppers, olives, capers, and raisins), all wrapped in a banana leaf, and cooked in boiling water. It's a food that takes an enormous amount of time and know-how--no rookies allowed here.

So, where did it come from?

The story of pasteles starts with European colonization, as many of these essays do. The Portuguese brought bananas and plantains (closely-related members of the Musa genus) to the Canary Islands from West Africa; a Spanish missionary then took the Musa plants with him to Hispaniola in 1516. They acclimated swimmingly to the climate, and it didn't take long for bananas and plantains to spread throughout the Caribbean and Central/South America.

Plantains quickly became invaluable as a staple food, but curiously, also gained a reputation as a lower-caste food. As early as 1597, Spanish documents mention plantains as a food ration for prisoners and the enslaved. Brother López de Haro wrote in 1644 that plantains were "rural y bárbaro"--the food of the enslaved and the poor. The 1826 Reglamento esclavista specifically listed plantains as a substantial portion of the daily rations for slave laborers. Plantains grew plentifully and required very little maintenance to produce a high yield, which curiously led to the stereotype that campesinos were disinclined to work, too indisciplined to fully exploit the land. Thus, those who ate plantains were painted as poor, low-class, unrefined country folks.

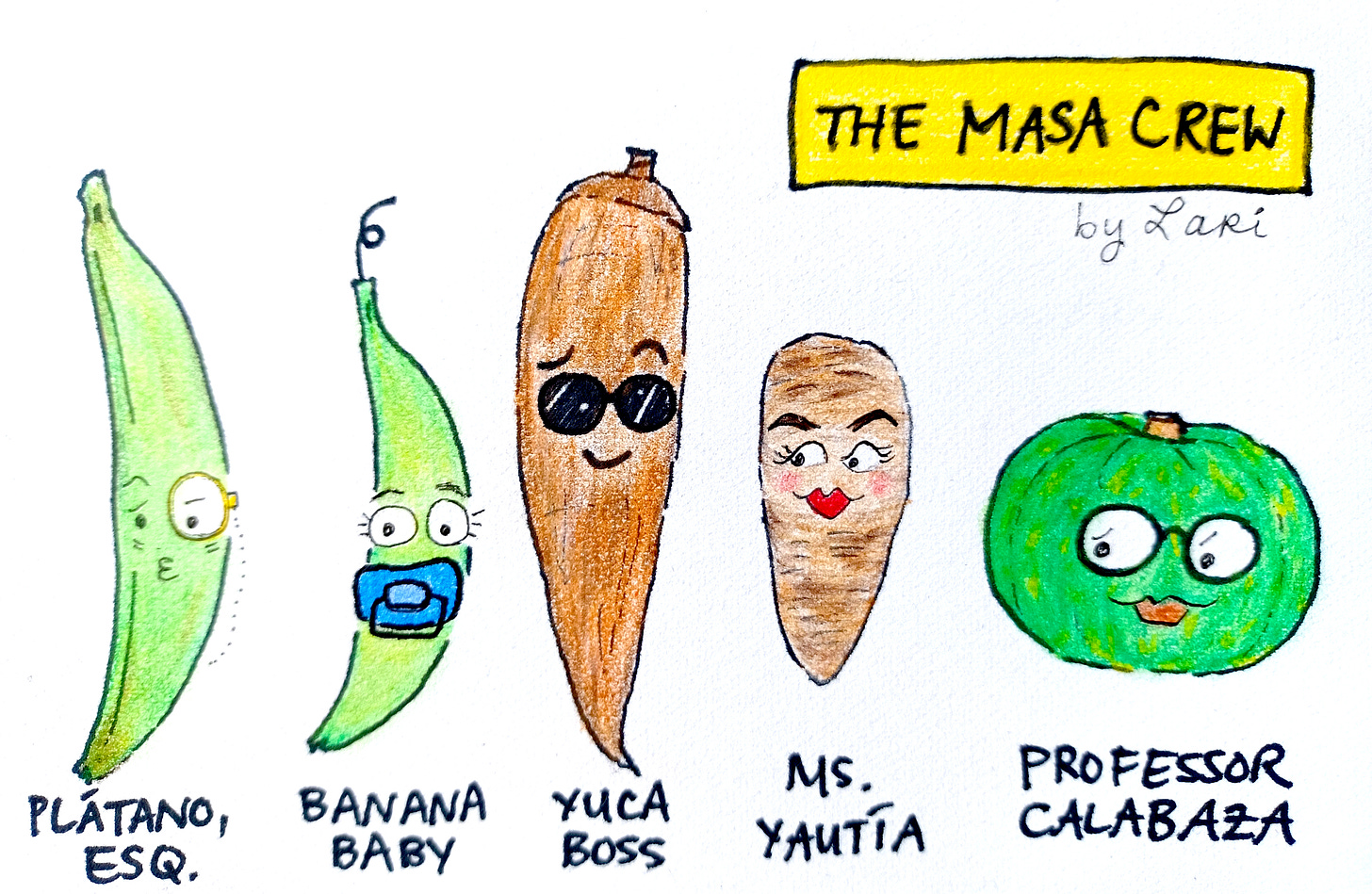

Moneyed individuals of privilege were the minority of the island's population, and much of the kitchen work (considered lower-class work) was often done by Afro-Puerto Rican and mestizo cooks. The base ingredients for their own food were the same they had to use to feed their bosses. So, we start to see dishes that become more labor-intensive, transforming and manipulating these "rural," "backwoods" ingredients into more "refined" dishes--these cooks mastered the preparation of the ingredients at their disposition. The African roots of pasteles are seen in the 3-step treatment of the viandas (be they plantains, green bananas, yautía [tannier], or otherwise): mashing vegetables into a dough, wrapping in banana leaves, and cooking the packages in boiling water.

19th century literature saw pasteles mentioned for the first time. The 1843 text El Aguinaldo puertorriqueño mentions pasteles as a traditional food for Three Kings Day, the holiday known to some as the Epiphany. It's not hard to imagine why: a delicious package to unwrap (like a gift) which takes much effort to prepare is a perfect dish for such a holiday. The first published recipe for pasteles didn't appear until 1931, in a home economics manual. This is no coincidence: the 1930's saw a redefinition of the idea of of puertorriqueñidad, or Puerto Rican cultural identity, of which food and culinary tradition play a major role.

Clearly, the know-how for pasteles had to be transmitted orally from cook to cook, from generation to generation. Between the dish's inception, to the first mention of pasteles in the 19th century, to the first published recipe nearly 100 years later, to today. It's a dish you have to learn to make from your elders, plain and simple.

Pasteles are more of a technique, rather than a fixed recipe. The composition of the masa, the use of achiote (or not), and the fillings are all totally up to the cook. The ingredients are of various origins, reflective of the history of Puerto Rico: Indigenous (yautía/tannier, chili peppers, achiote), African (banana, plantain), and Spanish (pork, garbanzo beans, olives, raisins).

In their TED talk, Zoe Adjonyoh discusses exploring their West African heritage and identity through food. The smell and taste of the food has the power to transport you home, connect you with a community, comfort you with delicious familiarity. In my own way, this rings so true.

Out of necessity and taste, I develop my own equivalents, processes, substitutions, flavors. I don't have ají dulce here in France, so I use piment végétarien. I can't find yautía here, so I use my own blend of vegetables for my masa (or, vegetable paste). I've evolved the recipe for pasteles in my own way, as has always been done. Creating the idea of "home," expressed through food.

It is hard to deny the importance of food in my own assertion of my puertorriqueñidad. I make coquito and pasteles at Christmastime, keep sofrito in my freezer and gandules in my pantry at all times. Hell, I write this newsletter: many of my food history essays have been an ongoing love letter to this rich heritage into which I was born.

There are many other dishes throughout the Caribbean and Latin America that resemble pasteles, including Dominican pasteles de hoja, Trinidadian pastels, Mexican tamales, and Venezuelan hallacas.

I've seen pasteles described as "Puerto Rican tamales," no doubt to draw a parallel with a food presumed familiar to a wider audience. I would rather describe them as "Puerto Rican meat pies," if I had to use a different phraseology. "Tamale" is a word of Nahuatl origin, and this dish was born from a Mesoamerican tradition. "Pastel" is a word of Latin origin, meaning "paste," and the dish was born from a marriage of West African cooking techniques with Indigenous Caribbean and European/Spanish ingredients. The two dishes resemble one another, but painting them with the same brush doesn't seem fair, in my humble opinion.

To see the pastel-making process yourself, I invite you to check out Jessica van Dop-DeJesus (aka. The Dining Traveler)'s Youtube channel: Pasteles de yuca (cassava) and Pasteluría (Pasteles and alcapurría).

I'll leave the video content to the less camera-shy among us!

What would you take with you if you were displaced from your home? Even those who would appear to be empty-handed are not: the resilience of the human spirit is partly in the knowledge taken along. Food and tradition tell the story of where we are now, where we have been, and where our ancestors came from. Understanding and paying respect to our history, our heritage, is (to me) part of puertorriqueñidad.

Another part of being Puerto Rican means being resilient. Through each and every hardship, you have to keep moving on. Remnants of that long struggle rub off on your children, and your children's children.

Growing up, I always knew that something was wrong. I was well-fed, had a roof over my head, and was excelling in school. So why was I struggling, drowning? I felt defective. Why did I want to destroy myself? I learned how to skate through and pretend that I was fine, while going home to quietly cry myself to sleep. I thought I didn't deserve to exist, and that God had made a mistake with me. My home was not always a safe place for me.

In our culture, you don't have the choice to not be okay. You have to push on to survive--work to make it through. I understand now I was in the care of a community that did not know how to spot red flags, or what red flags even were: not a sign of weakness, but a young person who needed support that never came.

Carrying the burden of generations before, on top of one's own baggage, is too much for one person. And it is hell to suffer in silence, to feel guilty for existing.

The elephant in the room threatened to suffocate me, and I had to escape. I was convinced that if I left, I could find that “something” that was missing, that I needed to be okay. I decided that any place that made me feel that way was not my home. With peace and love, I had to leave.

The first Christmas I spent away from home was in Japan. I was on a year-long academic exchange, and one of my Japanese friends invited me to her family's home for Christmas Eve. Christmas isn't a big deal in Japan, but my friend knew I'd be homesick. Her mother had prepared a gorgeous spread, including these tender, heavenly stuffed cabbage rolls that I still vividly remember, and she taught me how to make mochi (rice cakes). My friend and her mother showed me another idea of what "home" could feel like. (We are still friends, nearly 15 years later.)

My late grandmother was the one who taught me how to make pasteles--she was the only one in the family who knew how to make them. She taught me the technique, how to prepare each of the components, and how to wrap them for cooking.

From the time I was about 12, I consecrated myself to learning how to make the foods I so enjoyed eating. I needed to know what the ingredients were, what went into it, and how I could recreate it. I still have my cute notebook, instructions for dishes like sorrullitos and pasteles, written in loopy script and purple ink.

I referred back to that old notebook as I began developing my own recipe for pasteles, after I moved to France. It's taken years of practice, and while they're still not 100% perfect, I am proud of my recipe. I've taken a few liberties, added my own subtle touches to make it my own, because as we all know: even if you have the exact recipe of a heritage dish, you know it's futile to try and make it just the way they did. I figure, I'm better off keeping the spirit alive, rather than trying to chase after an ephemeral taste based off an even more ephemeral memory.

My grama understood me in her own way--her acceptance was never conditional.

I don't know what she was thinking about, but she and I could just sit together, in silence, and just be with our thoughts. Listening to her birds chirping, crunching into sorrullitos or bacalaitos, chewing into pasteles and white rice. Looking out the window together and simply existing, together. She'd hold her fork with those soft, careworn fingers that the arthritis progressively left more and more misshapen over the years.

Shaping the masa into form, I use the side of my hand before folding it together. My right pinky finger is permanently a bit bent--the result of a knife accident during quarantine. Today, looking down at my bent finger, sitting quietly in my apartment that smells like hers, I understand how important it is that I keep that beautiful essence of her memory alive.

Home is my own crooked finger pushing the pastel masa into place.

I have gently been settling into the reality that I will likely live outside the United States for the foreseeable future. I'm trying to understand how to stay connected to my own idea of "home," my family, and my cultural heritage. My Latinidad, my puertorriqueñidad.

When I got married, I decided not to take my husband's French last name. I chose to keep my maiden name, one I happen to share with the great Puerto Rican poetess (no family relation, we just share a name). I pronounce my name with the fluttery Spanish Rs that francophones always stumble over. In a way, it's my way of telling people: If you can't pronounce my name, you don't know me, and you don't belong in my world. (It's also my subtle "fuck you" to the French immigration system that pushes for assimilation.) It's a name with a heavy history that lives in my bones, in my DNA. But it's mine. Home is hearing my name pronounced correctly, and refusing to change it.

For those among us who struggle with the idea of "home," I'd like to put this idea forward: "Home," rather than being a place, or associated with other people, is more a state of mind. Inside yourself is a place where everything is clear, understandable, and all those things you don't know how to say don't have to be said.

To me, home is listening to music that touches my heart: hearing Hector Lavoe calling for us, la gente, to sing; and Célia Cruz reminding me that life is a carnival.

Home was my husband washing my hair in the sink for me when my arm was wrapped in a cast. Home is letting my hair down, putting my heart at ease, letting people help me.

Home is meditating while burning the incense that reminds me of that Christmas Eve with my Japanese soul sister.

Home is speaking a blend of languages and being understood.

Home is feeling safe enough to admit when you need help.

Home is the smell of pasteles boiling, and the film of steam that coats the kitchen window.

Home is starting new traditions, and continuing those that anchor me here, in this world.

Home is inside me: in these hands, in my bones, in that ancestral memory that one day, I will also be a part of.

Thank you for reading. I am proud to wrap up 2021 with this essay, the culmination of one year of this newsletter. If you enjoy my work and would like to support my efforts, share with a friend/hit the "like"/leave a comment to help this newsletter grow, and consider a paid subscription for yourself or a friend. I also accept one-time donations via my website. To follow my art practice, follow me on Instagram or my website.

Be well, take care of your heart, and I'll see you next month.

Bibliography

Davidson, Alan. Tom Jaine, ed. The Oxford Companion to Food, 3rd ed. Oxford University Press, 2014. p. 58-60, 630-1.

Duarte, Cristiane S et al. “Culture and psychiatric symptoms in Puerto Rican children: longitudinal results from one ethnic group in two contexts.” Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines vol. 49,5 (2008): 563-72. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01863.x

El Aguinaldo puertorriqueño de 1843. p. 203

"Food - A Cultural Stepping Stone | Zoe Adjonyoh | TEDxOxford." Youtube, Uploaded by TEDx Talks, 4 April 2019.

Gamayo, Darde. "How The First Puerto Ricans Arrived On Hawai’i Island." Hunter College Center for Puerto Rican Studies. Published with permission 14 September 2017. (Originally appeared 6 September 2017, Big Island Now)

Jimenez, Claire. "For Puerto Ricans, It’s Not Christmas Without Pasteles." Eater, 18 December 2019.

McGee, Harold. On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen, 2nd ed. Scribner, 2004. p. 139, 341, 378.

Ortíz Cuadra, Cruz M. Eating Puerto Rico: A History of Food, Culture, and Identity. Translated by Russ Davidson. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013. p. 31-2, 139-153.

Wharton, Rachel. "Pasteles, a Puerto Rican Tradition, Have a Special Savor Now." New York Times, 1 December 2017.

I don't know how you achieve this but when I read your essays it always touches my heart and I am overwhelmed with emotions. Thank you. I wish you all the best.

A wonderful, personal, touching piece. I loved it!