RENDERED 6: Genghis Khan (Jingisukan)

What sheep have to do with the Mongol Empire and Japanese imperialism

What does a 13th-century Mongolian warlord have to do with a 20th-century Japanese dish? "Genghis Khan" (Jingisukan) is a Japanese grilled mutton dish associated with the northern island of Hokkaido that was named after one of the most brutal conquerers in human history. From the name of the dish, to the meat itself, Jingisukan's roots tie in to Japan's colonial and military past, not only toward its own Indigenous people, but also during its Meiji-era modernization and identity crisis, and finally its expansionist campaigns of the 20th century.

The idea for this month's newsletter struck me as I was reminiscing about my time spent in Japan, and all the glorious food I've eaten there. I studied Japanese in college, studied abroad there for a year, and have since returned for multiple visits. One such trip was in February 2010, when I packed up my wool sweaters and spent a couple weeks there, in the thick of winter. I wanted to visit Hokkaido during the annual Snow Festival, and that leg of my trip was the coldest I have ever been in my life. So a piping-hot grilled meat dish like Jingisukan was exactly what I needed; it was the first time I'd eaten mutton, and it did not disappoint.

As it often does, my mind went to the questions: Why is it called "Genghis Khan"? Why is it so often associated with Hokkaido and Northern Japan? And why isn't mutton eaten more widely across Japan?

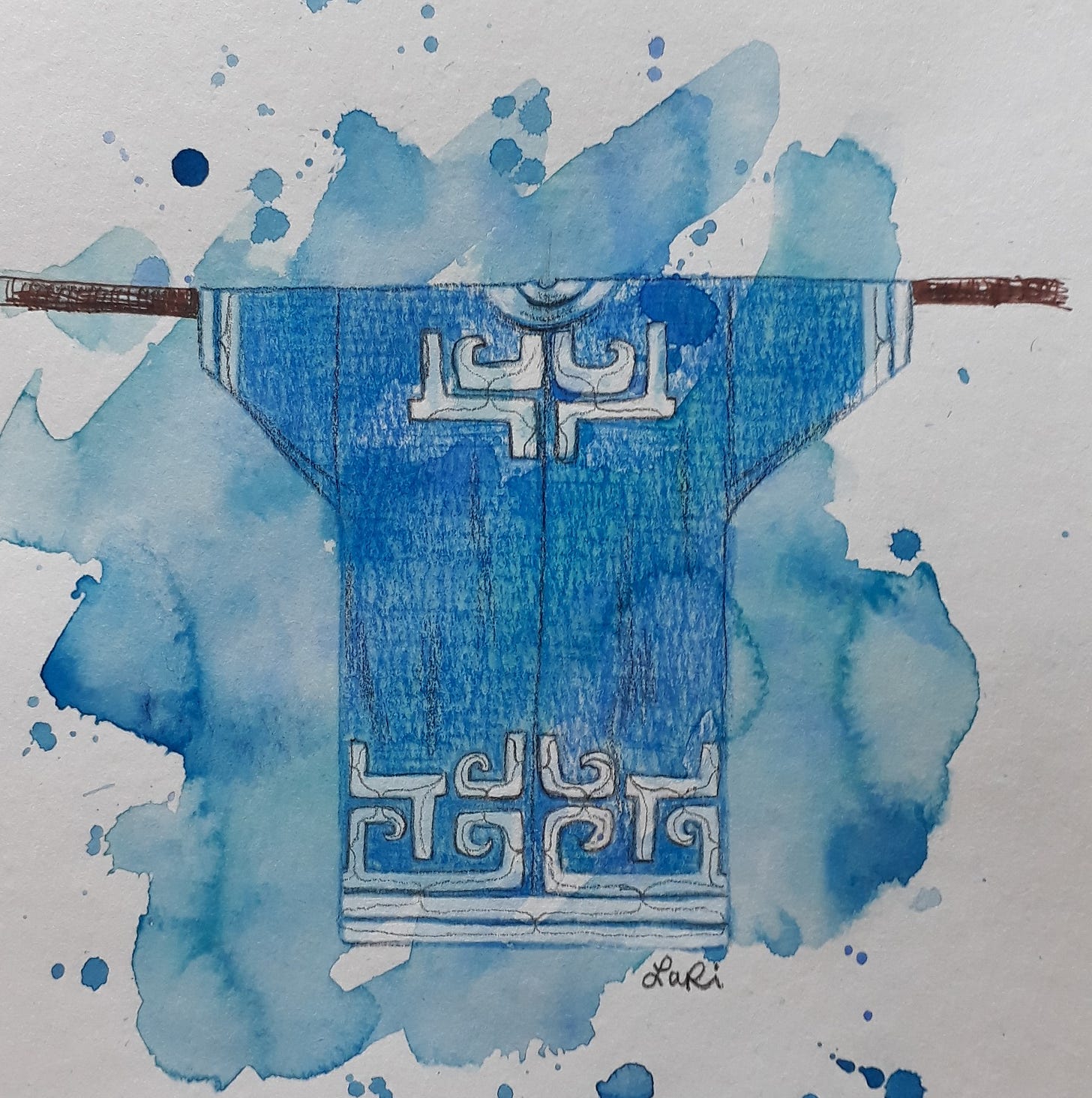

My interpretation of the Jingisukan I ate in snowy Sapporo, Hokkaido in February 2010. When it's served, there is a heating element underneath the dome-shaped pan, upon which you lay your vegetables and meat to cook to your desired level of doneness. Not pictured here is the tall stein of Sapporo beer that accompanied. A scrumptious flavor sensation that I remember fondly to this day. Jingisukan is cooked in a special cast iron pan with a raised center where the meat is grilled, and the vegetables cook on the side--it's said to resemble an army helmet. Cooking tip: in Takikawa (central Hokkaido), the meat is marinated in a mix of grated onion and apple, local ingredients that impart flavor and tenderize the meat before grilling.

Let's talk about the man himself. Some of you may be wondering: who was Genghis Khan?

The man we call Genghis Khan or Chinggis Khan (an honorific name, "Khan" meaning "leader/ruler") was born Temüjin near the banks of the Onon River in Khentii Province, northeastern Mongolia, around 1162. He was born into a nation of people leading nomadic, pastoral lives, forming tribes that were divided into clans spread across the steppe.

During his lifetime, he managed to unite the peoples of the central Asian plains by force, forming the Mongol Empire, using innovative and utterly ruthless military strategy to further invade new lands. He died in 1227, leaving his empire to his progeny, who carried on expanding the empire.

The Mongol Empire became known not only for defeating its enemies, but annihilating them and causing mass devastation in its wake. The Siege of Baghdad, for example, saw the destruction of the House of Wisdom--the Tigris River was said to run black from the ink of all the books destroyed. Up to 40 million people people lost their lives, including up to three-fourths of Persia's population, reducing the world population by as much as 11%. The empire, at its peak, stretched across Eurasia: it was the largest contiguous empire in human history.

Mutton isn't widely eaten in Japan today. Sheep weren't even introduced into the country until 1857, and so before that, there was simply no tradition of eating them.

Long story short, it all comes down to militarization. Sheep were originally brought to Japan to stock up on wool for uniforms and blankets, in preparation for decades of military aggression.

But I'm getting ahead of myself. We gotta get into some Japanese history here. From 1603 to 1868, Japan was run by a feudal military government called the Tokugawa shogunate. Under the Emperor and Shogun (ruler), Daimyo (landowners) ran their own regions, and samurai (military nobility) worked for them. With an exception for strictly monitored Dutch trading, all contact with outside nations was cut off from 1639. Radio silence to the world.

That is, until 1853, when Commodore Matthew Perry, an American with "Do you know who my daddy is?" energy and Presidential orders, showed up with guns blazing. His message: OPEN UP! OR I'LL HUFF AND PUFF AND BLOW YOUR HOUSE DOWN! And with that, Japan was brought back onto the world stage.

This new presence of foreigners (and foreign influence) in Japan caused major unrest, rebellions and uprisings, which ended with the resignation of the Shogun. This is the Japan that the first sheep arrived into.

The executive decision was made in 1867 to dissolve the shogunate, and completely restructure the country. Daimyo were either relocated, pushed into retirement, or given governor status of the new prefectures. Needless to say, the samurai were disturbed by this new order, and made their discontent known. One example of this was the Satsuma Rebellion in 1877, where "the last true samurai," Saigō Takamori, famously met his end.

Japan had entered a new era. The capital was moved from Kyoto to Edo (Tokyo). Territory was divided into prefectures, the way it remains today. Bye-bye shogunate, hello modernization: industrialization, banks, railways and telegraph systems, Western philosophy... and a shiny new restructured military. More taxes = more money. Conscriptions = more bodies. Japan had to show a new, stronger presence to the world, to play with the big boys. The Emperor made the message clear to anyone listening: "Don't mess with us."

The Meiji Era had begun.

Now, what does any of this have to do with Genghis Khan? Two things: practicality and identity.

First, the closed-door policy had, to the Emperor's mind, put Japan in the uncomfortable position to play make-up. The country couldn't appear weak on the national stage. But also, there was a bolstering of the entitlement that comes with power: why don't we show everyone how powerful we are?

This expansion of Japanese industrialism and military power, combined with the idea of divine right, led to wars with China and Russia, the brutal campaign of invasion and colonization of Taiwan (1895-1945) and Korea (1910-1945), the occupation of Manchuria (1931-1945), and many more.

All those soldiers needed to be clothed and supplied with blankets. Despite a research mission to the United States in 1871, and the recruitment of an American rancher to Hokkaido in 1873, sheep-rearing never really took off. Goals were set in 1914 and 1918 to increase production to 1 million head by 1925, but that goal was never reached.

So, what to do with all that meat? Grill it up!

In a 1931 book entitled "Wool Sheep and How to Raise them," there are 30 recipes for mutton--one of which was Jingisukan. It's not surprising, considering there was a general lack of awareness or custom about how to prepare mutton or lamb. The first first restaurant specializing in Jingisukan appeared in Sapporo in 1936, and since then, it has become an iconic northern Japanese dish. Today, there are about 16,000 head of sheep in Japan, half of which are in Hokkaido.

It's also important to note that Japanese expansion didn't start with the Meiji Restoration. The trial run was the occupation and annexation of Indigenous lands, and forced assimilation of the people: notably, the Ainu (in Ezo, Sakhalin and Kuril Islands), and the Ryūkyūan (Okinawa/Amami Islands).

The Ainu resisted encroachment into their territory repeatedly, culminating in a battle in 1789. After, the shogunate became more aggressive--from 1799 it straight up annexed Ainu territory, called Ezo (or Yezo) at the time. In 1869, the island was renamed from Ezo to Hokkaido (北海道, "Northern Sea Road"). The 1875 Treaty of St. Petersburg with Russia created a frontier that divided Ainu lands, displacing people, forcing them to give up spiritual practices, their language, and take on Japanese names. Their labor was also utilized to reform Hokkaido's agricultural landscape.

Part of the Meiji Restoration was to complete this colonization process, to perfect the vision of a "unified" Japan. From 1899 to 1997, the Hokkaido Former Aborigenes Protection Act was in place: the law declared that conquered Indigenous peoples lost their Indigenous identity once they were assimilated, which effectively created the illusion of a monolithic Japanese population. It wasn't until 2008 that the Japanese Parliament recognized the Ainu as an Indigenous people, followed by official, legal recognition in 2019. Their right to self-determination has yet to be granted. The Indigenous status of the Ryūkyūan remains under debate.

So why the reference to Genghis Khan for the name of the dish? It ties to the second point: the question of identity.

In a Japanese context, if you think "mutton," Mongolia is one of the first places to come to mind. And when you think "Mongolia," Genghis Khan comes to mind. (Of course mutton is widely eaten in Mongolian cuisine, but there is no dish called "Genghis Khan" that exists there.)

But, on a deeper level, there is a heroic vision of Genghis Khan that became artificially connected to Japanese identity that resurged at, coincidentally, critical moments in Japanese military history in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

During the Meiji Era, as Japan opened to the world, I mentioned earlier the need to put up a strong front, while simultaneously reforming the country from inside out. This is when the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs sent students abroad to study, particularly to England. One such student was Kenchō Suyematsu--the first person to translate Genji Monogatari (The Tale of Genji), one of the world's great works of literature, into English.

Perhaps out of the desire to show off, perhaps out of patriotic sentiment, he also published a book that asserted that Genghis Khan was actually... Japanese. In "Genghis Khan was Minamoto no Yoshitsune or Gen Gikei," he used thin logic and long-since refuted "evidence" to connect Genghis Khan to a legendary Japanese military hero, Minamoto no Yoshitsune. This hero on the battlefield died at the age of 30... or did he? Maybe he actually faked his own death (by ritual suicide), escaped to Ezo/Hokkaido, and somehow made his way to the central Asian steppe to become... Genghis Khan himself! ...Yeah, right. Sure, buddy.

The urban legend that Genghis Khan was actually Japanese resurged with another publication in 1924. Yet another disproven theory, bandied about on the eve of the Korean War, states that the ancestors of the Japanese Imperial Family were horsemen from Mongolia.

The desire to identify with this legendary, widely-recognized historical figure could have been a way to bolster an emerging nation's confidence. I mean, who doesn't want to descend from royalty? If the pride--and the reputation--of a nation is on the line, some individuals will be prepared to concoct a corresponding narrative. It's a cheap way to pull the wool over the eyes of the public, as the State drags them into decades of conflict.

Jingisukan is a dish that combines two importations that are relics of the country's military past: sheep for wool, and the image of Genghis Khan. While I doubt most people who eat the dish are aware of the story behind it, I think it's an interesting example of a dish that carries with it some heavy baggage.

It's a tired trope at this point to say that "Food tells a story." And if someone wants to eat some delicious Japanese mutton barbecue, I'm not gonna be the one to interrupt that gastronomic experience. But context is valuable. Why?

It's why I write this newsletter. The stories behind the food we eat are richly fascinating, yet often sobering. We're reminded that the things we eat, if you go back far enough, come from legacies we had no hand in creating. We are pushing toward being conscious consumers, and to me, that also means contextualizing the history of what we eat, why we eat it, and how it landed on our plates and into our collective culture.

Thanks very much for reading. If you liked what you read, please like, comment, and share with a friend. If you’re interested in contributing financially, you can consider becoming a paid subscriber for bonus content: TIDBITS: narrated essays released on the 1st of every month, accompanied by one illustration. Previous TIDBITS subjects include Spanish Fly, comfort food, and the history of the Whiskey Sour cocktail.

Be well, take care of yourself, and I’ll see you next month.

Bibliography

Andrews, Evan. "10 Things You May Not Know About Genghis Khan." History.com. 29 April 2014 (Updated 29 July 2019.)

Blakemore, Erin. "Who Were the Mongols?" NationalGeographic.com. 21 June 2019.

Broadbridge, Anne F. "The rise and fall of the Mongol Empire." TED-Ed, Youtube. 29 August 2019.

Delgado, James P. "Khubilai Khan Fleet." Archaeology.org.

Fogel, Joshua. “Chinggis on the Japanese Mind.” Mongolian Studies, 30/31, 2008, pp. 259–269. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43193543

"Indigenous peoples in Japan." International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, IWIA.org/en. 18 March 2021.

"Japan's encounter with Europe, 1573 – 1853." Victoria and Albert Museum, Vam.ac.uk.

"Jingisukan (‘Genghis Khan’ – Japanese-style grilled lamb)." NHK. 12 September 2014.

Kay, R. "Sheep Raising in Japan." Pacific Rural Press, Vol. 21, Number 4. 22 January 1881. California Digital Newspaper Collection.

KWANTEN, LUC. “For a New Biography of Chinggis-Khan.” Mongolian Studies, vol. 3, 1976, pp. 126–130. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43193038

Low, Morris. “Physical Anthropology in Japan: The Ainu and the Search for the Origins of the Japanese.” Current Anthropology, vol. 53, no. S5, 2012, pp. S57–S68. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/662334

"Meiji Restoration." Britannica.com.

MIYAWAKI-OKADA, JUNKO. “The Japanese Origin of the Chinggis Khan Legends.” Inner Asia, vol. 8, no. 1, 2006, pp. 123–134. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23615520

Shinichirō, Takakura, and John A. Harrison. “The Ainu of Northern Japan: A Study in Conquest and Acculturation.” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 50, no. 4, 1960, pp. 1–88. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1005795

Walker, Brett L. “Meiji Modernization, Scientific Agriculture, and the Destruction of Japan's Hokkaido Wolf.” Environmental History, vol. 9, no. 2, 2004, pp. 248–274. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3986086

Yajima, Azusa. "Why did 'Genghis Khan' become so popular in Hokkaido?" KAI Hokkaido Magazine.

Hugely interesting piece. And amazing illustrations. 👏🏻👏🏻👏🏻