Hello and welcome back to RENDERED. We are, once again, in the "light" half of the year, meaning cyanotypes are once again possible, the sun sets at an appropriate time, and I am filled to bursting with creative juices. This essay is an exploration of a new artistic endeavor that I’ve been working on for the past few weeks. Enjoy.

Wintertime means a lot of brown food. Even if I throw in some greens or frozen vegetables, the cloudy daylight makes everything look grayer, slightly dingier. Lentils, potatoes, saucy simmered dishes, even roasted vegetables and vibrant sauces fall victim to the muted grayness. Maybe that's why I’ve found myself, especially this past winter, painting with brighter, more fluorescent colors. In the food I make, the art I create, and the decor I like: color is the keyword. I may wear mostly black myself, but I desire everything I touch to be colorful.

This led me to experimenting with a craft that combines food and color: inkmaking. For this month's RENDERED, I created four inks from kitchen ingredients. Each one is unique, and has satisfied my itch for color.

When it comes to food, it ain't no stranger to added coloration. Colorants, ranging from natural to straight-up toxic, have been in use for as long as food has been sold. Artificially zhuzhing the color of a foodstuff makes it more attractive, and stay that way longer. It is through legislative records on food adulteration that we realize the lengths to which unscrupulous merchants went in order to pad their profits. In 14th century England, for example, cinnabar (a vivid red, poisonous mercury compound) was added to cayenne pepper to keep its color bright.

Rather than artificial colorants (which is a totally different discussion), I'm focused on raw ingredients. Natural food colorants are everywhere: achiote, squid ink, ground black sesame, berry juice, paprika, turmeric, ube (aka. purple yam), cocoa, spinach, saffron, red cabbage, beets...

If we eat first with our eyes, it stands to reason that we respond to the color of our food. It is part of that which sparks the appetite, how one evaluates edibility, how it measures up to what one is accustomed to.

While I was living in Korea, I came to learn about obangsaek: the traditional color theory that extends to meals. The five cardinal food colors are white, black, yellow, green, and red--and a balanced meal should contain all of them.

My first brush with Korean food colorants was on Chuseok, the autumn harvest festival that (for better or worse) gets equivocated to US-American Thanksgiving. My landlord left a small bag of songpyeon, or half-moon shaped rice cakes, on my door handle. They were dark green, and tasted of pine--now I know the green color likely came from mugwort powder.* An unexpected flavor from an unexpected kind gesture.

In Japanese cuisine, you have umeboshi--pickled sour plums. When they're homemade, the plums are preserved in salt and red shiso leaves, which impart a lovely flavor and deep pink color. The flesh is extremely tart and salty, making a perfect filling for onigiri (rice balls wrapped in seaweed). My favorite flavor!

If color speaks to me in such a way via food, why not infuse the two? I set three rules for myself in this inkmaking project:

1. to use cooking ingredients I already use in my kitchen;

2. to use materials recycled from my kitchen; and

3. to use supplies readily available from my local shops (food and art)

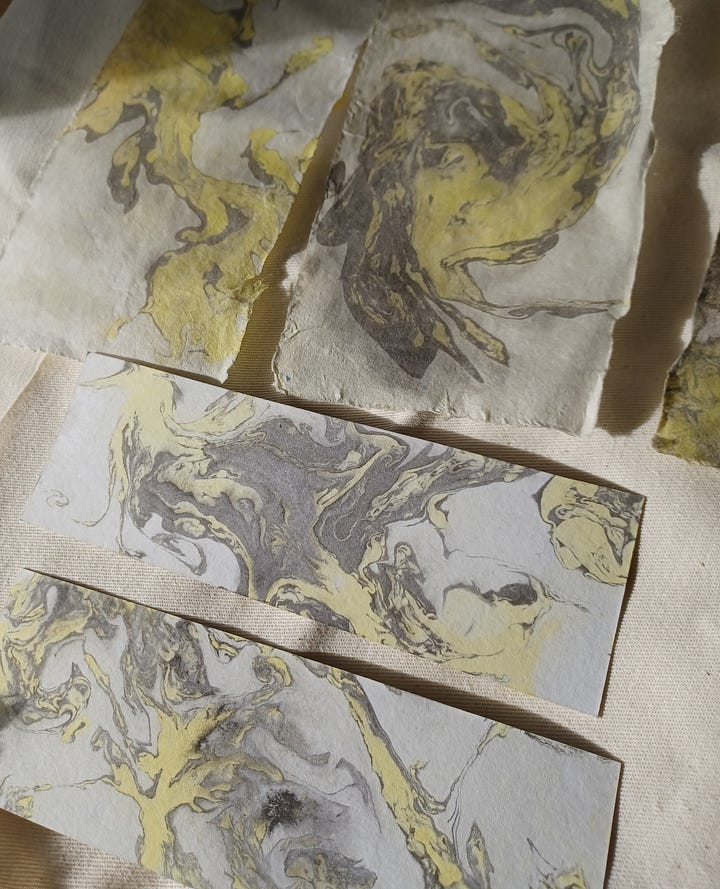

Those who follow me on Instagram have seen some of my trials (and errors), but I now possess 4 bottles of natural ink. Here they are:

Turmeric

My first attempt was the simplest ink: turmeric alcohol-based ink. It produces a vibrant, almost electric yellow that fades quickly in sunlight. The charm of this highly fugitive pigment lies in the pleasure of witnessing its application. With this early success, I felt emboldened to continue my kitchen ink experimentations.

Turmeric (Curcuma longa) is a rhizome (like ginger), native to India and Southeast Asia. It has been used medicinally for about 4000 years, and is commonly used in Ayurveda.

It has been traditionally used in cosmetics, food and drink, and as dye. Also known as haldi, it gives its color to Buddhist robes in some monastic traditions, and is used in Hindu wedding customs. In food, turmeric lends its yellow color to condiments, curry powder, mustard, and more.

When Marco Polo came upon it in China in 1280, he likened it to saffron, likely due to its color. And so, it came to be known as "Indian saffron."

Avocado

For this ink, I wanted to show some love to some rather dusty, bone-dry avocado pits that had been sitting in my kitchen windowsill for longer than I'd care to admit. (I do have a hard time throwing things away, especially when I can envision some artistic use for it.)

Simmering in water with a couple extra ingredients, the pits first gave off a pale neutral brown. The water slowly went mauve, then deepened into a syrupy reddish-purple/brown.

Avocadoes contain anthocyanins, which are reddish pigments also found in fruits such as blackberries and black elderberries. These are water-soluble pigments that can change according to pH levels. (This gives us braised red cabbage that tinges blue, and garlic that turns green or blue when pickled.)

Avocado seed dye has a long history in Latin America. Some documents of the Spanish conquest were penned with avocado seed ink; the Guna (Indigenous Panamanian) creation story mentions avocado dye; and alpaca and llama wool dyed with avocado has been found at archaeological sites in the Andean highlands.

Shallot Skins

To make this ink, I re-used the water from my first two failed attempts at achiote ink. Over low heat, I threw in shallot skins I'd been squirrelling away for weeks in a brown paper sachet. The skins shriveled and cooked down, then were strained. The resulting ink has a pleasant granulating quality.

Achiote (Annatto)

When I wrote my essay on the history of annatto (called achiote in Spanish or roucou in French), I mentioned its common use as a food colorant in dairy products, as well as its use in Puerto Rican cuisine, and my own personal attachment to this ingredient.

Being able to find it in my local import market here in France meant that I could recreate my Puerto Rican recipes more faithfully--especially for pasteles and rice. My late grandmother relied on achiote for its color (rather than commercial sazón seasoning mixes with artificial colorants)--many times I watched how she melded the seeds gently into oil, then strained them out into a Corelle coffee cup, always using the same ol' little strainer, its errant wires coming undone at the sides.

Anyone who's used it also knows: it stains like crazy, so do not wear nice clothes when working with it!

Getting my hands on achiote seeds here in France, combined with my interest in the intersection of plants and art (cyanotypes, eco-printing, papermaking...), meant inkmaking felt like a natural next step. Emboldened by the success of my debut batch of turmeric ink, I tried achiote.

It turns out, this achiote ink was the most difficult to obtain a satisfactory result, despite the fact that it's the kitchen ingredient I've known the longest. Powdered achiote versus whole seeds, water versus alcohol, heat versus no heat, steeping, repeated cycles of swatches and lightfastness tests... 3 ink batches yielded just 1 satisfactory product.

I suppose I could have sought more info in my research. I could have just bought achiote ink from a more practiced artisan and called it a day. But as is my way, I need to get my hands in there and find out for myself. Good ol' trial and error. (You know--the journey, maaan!)

Making takes time. And I had a lot to think about during those in-between moments of waiting.

The process of "making" is that liminal space between Idea and Finished. That is the space where learning and feeling happen. The only way to see if my idea will work, is to traverse the unknowing process of making, without wishing it away to rush to a final result to put on display. Unfortunately, not every attempt gives social media-worthy results. Sometimes, results are unexpected, unremarkable, or downright disappointing.

This came to be the background chorus of my trials and errors in the studio, playing with water and pigment. Greeting disappointment with curiosity and patience. A conversation between my brain, hands, and raw material, that exists in that liminal space.

I'm about to leave for a trip to see my family in the US. Before every trip, I make a journal that will hold my anecdotic scribblings and sketches. I often sew myself a little bag from my collection of fabric--I piece together swatches that each hold a feeling. The time I take before each trip to make those items has become a pre-departure ritual--moments of anticipation and excitement, reflection, emotional transition.

It's comforting to wear my handmade jacket from inherited fabric, to interact with objects I created according to my exact taste. I can create a portable space of comfort and care, and acknowledgement (reminder) that I am capable. This makes it easier to give myself to the eventual, inevitable return to greeting disappointment.

Who knew that playing with food pigments in search of color would afford me the chance to practice giving in to patience and curiosity.

Thanks for reading. I'll be back next month with a new TIDBITS for paid subscribers, followed by the next RENDERED essay in mid-June. You can follow my art journey on Instagram and Youtube. My web shop will be on vacation mode from tomorrow (April 17th) until May 11th. Be well, take care of your heart, and I'll be back for paid subscribers next month.

RENDERED is a one-woman production, and your support is appreciated! If you're hungry for more content in audio format, consider a paid subscription. For 5€, you can get a month's worth of access to my narrated essay series, TIDBITS. Yearly subscribers get a logo sticker and art zine “The Best of RENDERED,” and Art Collectors receive a custom painting.

* Korean cooking legend Maangchi has a recipe for songpyeon, including recommendations for natural colorants: gardenia fruits for yellow, and mugwort powder for green.

* The book Make Ink by Jason Logan has served as my main reference for my forays into inkmaking--it is a gorgeously photographed book! The Toronto Ink Company, founded by Logan, has an Instagram full of luscious ink swatches.

Bibliography

Davidson, Alan. The Oxford Companion to Food, 3rd ed. Oxford University Press, 2014. p. 5, 210, 838-9.

McGee, Harold. On Food and Cooking : the Science and Lore of the Kitchen. Scribner, 2004. p. 281, 430.

Prasad S, Aggarwal BB. Turmeric, the Golden Spice: From Traditional Medicine to Modern Medicine. In: Benzie IFF, Wachtel-Galor S, editors. Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects. 2nd edition. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; 2011. Chapter 13. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK92752/

Verde, Isvett. "Avocado Dye Is, Naturally, Millennial Pink." The New York Times, 15 Jul 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/15/fashion/avocado-dye-is-naturally-millennial-pink.html