Hello, and welcome back to RENDERED. If you're joining back after skipping last month's essay, welcome back. This month's essay is a bit late, and I must excuse myself--writer's block got me good this month. I also have an announcement to make about my web shop--more details on that at the end of the essay. For now, let's get into our topic for this month.

Christopher Columbus famously tried circumnavigating the globe to get to the Spice Islands via the Atlantic in the name of Spain--he landed in the Caribbean, which spurred a story we are all familiar with by now.

From Columbus's journal entry on October 21st, 1492:

"I shall then shape a course for another much larger island, which I believe to be Cipango, judging from the signs made by the Indians I bring with me. They call it Cuba, and they say that there are ships and many skilful sailors there."

We know that he called the people he met in the Caribbean "Indians" in a famous case of mistaken identity. But what is "Cipango"? This is what Europeans called Japan.

On October 26, 1492:

"I departed thence for Cuba, for by the signs the Indians made of its greatness, and of its gold and pearls, I thought that it must be Cipango."

Why was Columbus convinced that Cuba (or, what he thought was Japan) was rich in gold and pearls?

The answer sits among those possessions of his that are preserved today. Stored at the Biblioteca Colombina in Seville, it is inscribed with nearly 100 margin notations in Columbus's hand. This was a book that influenced his campaigns: Libro de viajes, or Il Milione, also known as Divisament dou monde (Description of the World), or as we know it today: The Travels of Marco Polo.

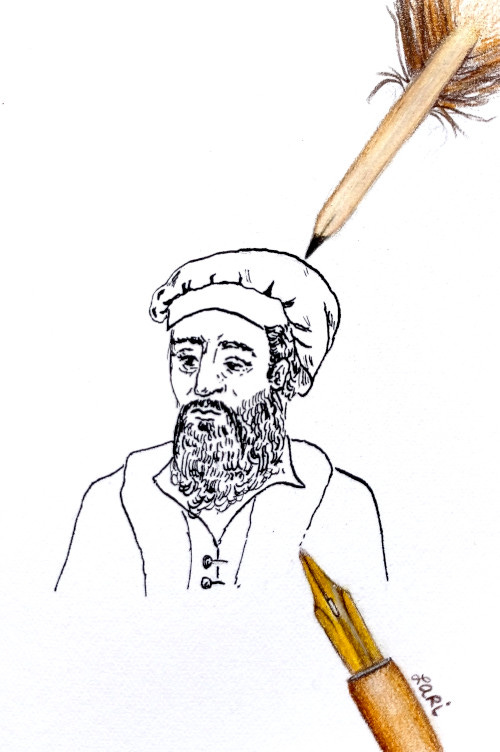

Marco Polo, the famous Venetian that supposedly brought the West to the East, was the first European to visit China, and the guy who brought pasta to Italy. Marco Polo, whose name has been shouted by generations of summering kids frolicking in swimming pools, and whose reputation as an intrepid traveller has inspired centuries of hoopla and intrigue.

But why? What about his work inspired (at least partly) the European desire to seek conquest, brutalizing and stealing from those they met along the way?

The answer starts with a Venetian blueprint.

Venice: A Brief History

Venice was founded by reclaiming marshland, likely by people who had fled the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century CE. The salt water lagoons were transformed into a city. As such, salt and seafaring trade were what Venice had to offer--there was no land to impose a feudal system on, and no agriculture, so the sea was the only option. Monopolizing the salt supply contributed to its early growth, but sailing was the vital key.

Venice is the early example of mercantilist capitalism in Europe. The government held the value of trade above all else. Profit was key, trade came before all else. Everything was for sale: art and music, religious relics, and war materials were seen as commodities. Venetian merchants took to the sea, and dodged political and civil unrest, conflict and war, creating trading posts in the name of expanding trade.

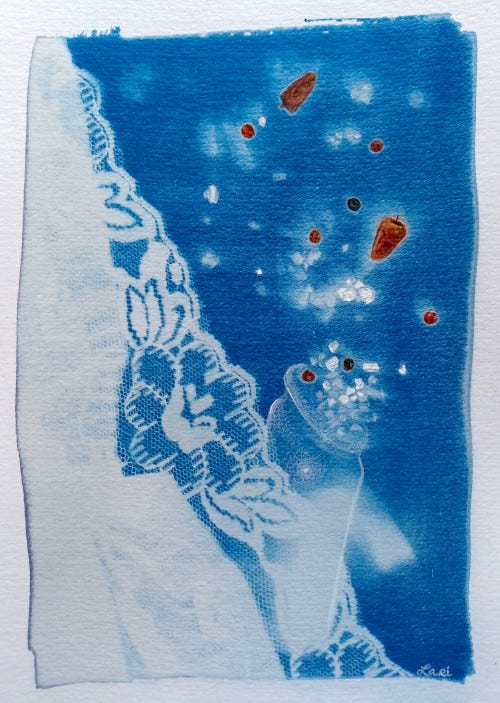

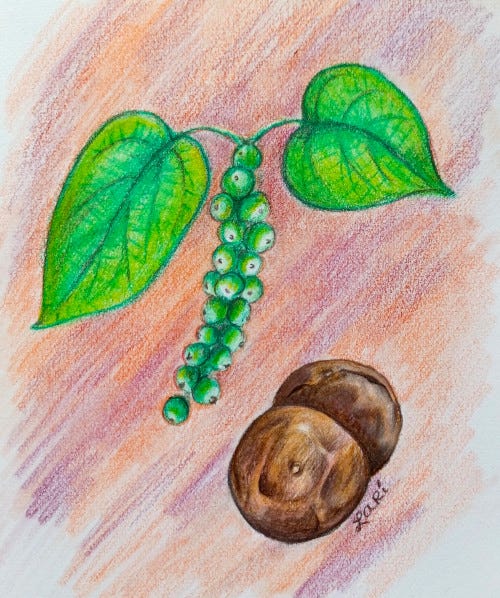

One of the top commodities sought during the Spice Trade was pepper. Native to the southern Indian subcontinent, pepper was traded with merchants in the Arabian Peninsula from 1800BC. As trade routes developed through both land and sea, the spice became more widely traded in Asia (via the Silk Roads), Persia, the Mediterranean and beyond. Medieval Europeans got addicted to the stuff, using it for flavoring, preservation, medicine, and as a status symbol: the price to the consumer for black pepper cost up to 40 times more than the source cost. Cutting out the middlemen to get pepper and other spices was one motivation behind the Spice Trade. Pepper made Venetian traders boatloads of profit--in the 12th century, a pound of pepper had the same monetary value as a week of work from an unskilled laborer.

Trading context

For Venetian merchants, travel was part of the deal--it's what everyone was doing. In this hierarchical society, money was linked with status, and sea trade was where the money was at.

Venetians were in Alexandria by the 9th century, which opened up marketplaces for luxury items from Asia: silk, gemstones, spices, and more. The Crusades led to an increase in demand for timber, textiles, grain, slaves... more war, more money! The Crusades were great for business.

The slave trade in 12th-century Venice was booming; Russians, Greek Christians, Armenians, Georgians, and other people captured around the Black Sea were brought to Venice, then sold to various Venetian patrician families, or to foreign buyers in Egypt, Morocco, Cyprus, and Crete.

Venice coordinated the sack of Constantinople (aka. modern-day Istanbul) during the Fourth Crusade in 1204, looting and pillaging the city and taking over this key trade location. (I admit, I can't use the word pillage without thinking of Nandor the Relentless...)

Notably, the four horses from the Constantinople hippodrome were placed outside St. Mark's Basilica (where replicas stand today). The body of Saint Mark himself was said to be smuggled out of Alexandria and into the city by some Venetian traders in the 9th century.

Constantinople opened doors to Asia Minor (Turkey today), Persia (Iran) the Mongol Empire (Central Asia/Mongolia/China), and beyond.

In 1211 Venice swooped in to take over the island of Crete, making it a colony in 1211, and holding on to it for over 400 years. It was a prime location for trade, and was used for labor in manufacturing. Overseas lands along the way to Crete were wrapped in the fold of the lucrative Venetian trade industry.

Mastering the production from raw material using refined artisanal skill: one example being glassmaking. Manufacturing, creating more refined items from raw materials, would increase profits and keep Venice at the top. From the 15th century, Cyprus was under Venetian control--techniques in making soap, glass, silk, and paper had been learned from the Middle East, the knowledge of silk and paper had been learned from China in the 8th century.

Venice dealt in trade of both everyday and specialty items from Egypt to the Far East, distributing these to Europeans who were hungry for more.

This is the world in which the Polo family rises to prominence. Daddy Niccolò and Uncle Maffeo had already made a name for themselves as traders, and were well-traveled. They had been to Asia, garnered favor with the ruler, Kublai Khan, becoming his ambassadors to the Pope. (Kublai Khan was the grandson of Ghengis Khan, whose culinary legacy in Japan I have written about previously.)

At age 17, Marco set out to the Mongol Empire with his father and uncle. They were gone for 24 years, 17 of which were spent doing their patron's bidding, going on fact-finding missions, and completing administrative duties in different regions of the kingdom, across the continent. On the return sea trip to Europe, they got robbed along the way, and made it back to Venice in 1295 with the clothes on their backs... and the gemstones they had concealed on their person. No spices, no gold, no silk.

Part of me asks, where were the women travelers?

Venice wasn’t the freest place to be a woman.

14th-century Venice was male-dominated society that valued patriarchal lineage and dedication to the state (and money). Inheritances passed from father to son(s), and daughters had dowries. Marriage was a tool to secure the family line, to maintain or improve social and economic standing--daughters were married off to that end. Women were largely relegated to the home, under the legal guardianship of either a father or a husband. Church services were divided by gender. In portraiture art of the day, women were nearly fully excluded, except for depictions of the Virgin Mary. Women had little legal autonomy to participate in society and the economy.

Legal statutes reflected the gender gap, in statutes on corporal punishments, for example. But there were many patrician women who had certain rights expanded over time. A woman could sue her husband for alimony to live separately, if she left him for mistreating her. Women helped interconnect Venice's most powerful families, gaining both social leverage and economic strength (in the form of higher dowries) along the way.

You might be familiar with the trope of the Venetian woman on a balcony. The balcony was indeed a semi-public place for Venetian women to see others and to be seen, to interact with the world in a limited way.

Marco Polo commented that women in China do not "hang out at the windows" to look out at people, as much a compliment to what he perceived as modesty, as much as a dig to Venetian women.

Scholars are still not clear on the true scope of women's business involvement--there is surely a gap between what they could do legally, and what they really got up to. People always find a way to work around closed doors.

We do know that they invested in business, worked as artisans, tradeswomen, and prostitutes. Just after Polo's time, from 1358 to the 16th century, prostitution was legalized in Venice--women were favored to run the places, and the people who worked there served a role in local society. This was done in the years after The Black Death, perhaps for the State to gain some control over forces of "disorder," bring in some cash flow, and keep visiting foreign merchants entertained, and coming back for more. One prominent 16th century writer, Veronica Franco, was a Venetian courtesan-turned-public figure.

Speaking of courtesans, Marco Polo does spend a fair amount of time describing the women he meets during his travels. He mentions the "fascinating," "bewitching" nature of the courtesans he met in Hangzhou, which he calls Kinsay.

Why do we call it "the Silk Road"? The term was coined by German academic Ferdinand Von Richthofen in a work from 1877, chronicling Chinese geography. In this same work, he spoke unfavorably of Chinese academics, and later in his career, went on to become a consultant in expanding Germany's imperial expansion into China. Oh, and this "expert" on China never learned Chinese--he relied on translations and did some fieldwork.

He used the term "Seidenstrasse" ("Silk Road") to refer to one specific trade route, from the Mediterranean to Chang'an, where silk was just one commodity exchaged.

What we call "the Silk Road" is really a network of trade routes that, at different points in history, connected cities across North Africa, the Middle East, and Central, Eastern, and South Asia. Certain sections of the Silk Road are listed as UNESCO World Heritage sites today.

Not only material goods (like silk, spices, porcelain, precious stones, tea, manufactured goods), but ideas traveled along these routes (religion, artisanal know-how...) For safety in numbers, people traveled in caravans through some punishing landscapes, stopping over at rest points along the routes called caravanserais, or inns where travelling merchants could hang their hat along the way. (I can't type "caravanserai" without thinking of this song by Loreena McKennitt.)

Venetian and Genoese militias had been clashing over the power to control valuable trade routes, and like a true Venetian statesman, Marco Polo contributed funds to the war effort. Unfortunately, he found himself himself captured at the Battle of Curzola (in today's Croatia) in September 1298, and thrown into a Genoese prison. Alongside him in jail was a romance writer named Rustichello (or Rusticiano) of Pisa. Polo got to chatting about the good ol' days, and Rustichello wrote down the verbal account of Polo's reminiscences. This account served as the basis for the book, but the original text by Rustichello has been lost.

The text saw some editing and re-writing by Polo and others, before being released to the public. It was released in 1300, the original language likely being Franco-Italian. At a time before the printing press, when books were hand-transcribed, most texts were religious. This was a totally different kind of book, a detailed travelogue-cum-memoir written in a conversational style.

The book was a hit, and people were hungry to learn much more about the lands to the east.

To be clear: the book is full of bullshit—there is a lot of exaggeration, spouting of complete nonsense, and artistic license run amok. Some scholars think he never even got to China: Why isn't Marco Polo mentioned in any historical records in China? Why didn't he talk about things like the Great Wall, tea, and porcelain if he really was in China?

Well, he might have gone by a different name in the Mongol court. He didn't learn either the Mongol or Chinese languages, so he kept to interacting with other traders, and translators. He wasn't terribly interested in local culture--he was a businessman, not an anthropologist. The Great Wall of China also didn't exist then in the same way it does today--major construction on the Great Wall took place after Polo's travels, during the Ming Dynasty.

The entire book can't be debunked. He wrote about animals like crocodiles and rhinoceroses, which he likened to mythical creatures. (Hey, the guy wasn't very highly educated, and he had never seen them before.) His book mentions paper money, coal burning, and a high-speed courier system, novelties he had seen in China.

We know circumstantially that he had to have been telling the truth about working in the service of Kublai Khan. Some parts of his story are completely accurate, and thus, believable. Other parts, he clearly made up (cannibalism in Japan, for instance). The rest sits in a weird gray area. According to him, though, it was all true. On his death bed, Marco Polo supposedly said "I did not tell half of what I saw." Okay, pal.

The book was translated into languages like Venetian, Tuscan, French, German, and Latin. Some written by professional scribes, others by amateurs. There are about 140 versions of this book in a dozen languages and dialects, all translated throughout the years with varying levels of care and authenticity.

The urban legend that claims Marco Polo brought pasta from China to Italy comes from a mistranslation.

The Antwerp edition of Marco Polo's travelogue published in 1485, written in Latin, was the edition Columbus got his hands on.

Polo's travelogue describes places he visited like Persia, Mongolia, India, Sri Lanka, Java, Sumatra, and more. But he also talked about places he'd never been, notably a strange island of immeasurable wealth: Japan, or as he called it, Cipangu. In Polo's hearsay version of Cipangu, the people are "white, civilized, and well-favoured"; that there were "endless" amounts of gold, pearls, and precious stones there. Polo describes the Emperor's palace as a literal palace made of gold.

This passage is what got Christopher Columbus hot under the collar, and impatient to find the riches Polo had promised were there.

On December 24, 1492, Columbus writes:

"[...]among other places they mentioned where gold was found, they named Cipango, which they called Civao. Here they said that there was a great quantity of gold [...]"

He arrived on Kiskeya (or Hispaniola), thinking it was Cuba, which he mistook for Japan. Are you following this nonsense? In fact, the Taíno (the Indigenous people) he was speaking with were referring to Cibao (or a northern region of today's Dominican Republic), a fertile valley that Columbus quickly colonized, renamed La Vega Real, and tore apart looking for gold.

Columbus was far from the only European to take notes from Polo's work. Others, including John Cabot, also used the geographic information in the book to try and find ways around the Arab-held trade monopoly, during the "Age of Discovery."

Was Marco Polo the first European to go to Asia? No, not by a long shot. We know, through written records and archaeological findings, that Chinese trade existed with Western powers for millennia before Marco Polo came onto the scene. Han China had been trading with the Roman Empire from in the second century BC, and Greek sculpture may even have directly influenced the creation of the Terracotta Army.

There is also a rich history of Sino-Persian exchange via the Silk Roads starting from about 126BC (perhaps I'll write about it in a future essay...) It was really Polo's book, rather than his own accomplishments, that goaded European interest eastward.

Columbus describes the moment where he made the grand proclamation before the people they saw when they arrived: the act of verbally proclaiming ownership of this new land, in a language that no one understood, holding symbols like insignias, initials, flags that were unintelligible, while brandishing the tools to enforce this newly invented reality.

In his writings about this event, he uses two devices to bridge the gap in logic to justify his forceful seizure of these lands. First, he writes: "no me fue han contradicho" ("They did not contradict me.") We see language used as leverage, to gain legitimacy and power. Giving oneself permission to do so, by invoking language.

The other justification is "wonderment"--the dazzling spectacle of confused silence that, in his own logic, signalled acquiescence. Columbus's language, like in Polo's travelogue, employs terms of wonderment to describe unfamiliar surroundings and new people.

While there's not a treasure trove of substantiated food history associated with Marco Polo, his "writings" framed beliefs about the East for centuries yet to come.

In all fairness, I'm not sure I blame him--he might have been talking out of his ass to kill time in jail, without realizing the impact his book, and its various translations, would have.

This brings me to ask: Who do we allow to frame our beliefs, what we think we know to be true? What forms the lens through which we see foreign cultures and peoples? How do we view ownership of ideas and know-how, and what informs our entitlement to it?

Context gives us the tools to decipher a real message behind a picture depicted by an author. Historiography (the study of the writing of history), and historicity (historical authenticity) help us gain a clearer picture of what happened, despite textual and academic bias.

Wonderment can be a feeling of mysterious, intriguing allure. It can be a blinding feeling that sweeps us up, obscuring myth from reality, and fact from fiction. Some myths, we continue to live with: How we view cultural heritage, gastronomy, our own histories, and so much more.

These ideas come from somewhere, and it's worth questioning how we know what we know, and where our knowledge comes from. It's not about finding who's telling the truth, but about reading between the lines.

Thanks for reading. If you enjoy my work and would like to support my efforts, share with a friend/hit the "like"/leave a comment to help this newsletter grow, visit my web store, or consider a paid subscription for yourself or a friend. I also accept one-time donations via my website. To follow my art practice, catch me on Instagram or view my portfolio on my website. Be well, take care of your heart, and I'll see you all next month.

Web Shop Update: I'm pleased to offer readers of RENDERED a discount on my web shop! From now until August 1st, use the code RENDERED10 for a 10% discount on your purchase.

Paid subscribers: a 20% discount code is coming on June 1st, so stay tuned. I add new pieces regularly, so if you're interested in purchasing a piece of art (or just browsing), visit my Etsy shop here: https://www.etsy.com/shop/larisanjou

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Venice: Pure City. New York: Anchor Books, 2009. p. 37, 79, 102, 105-6, 267, 270-71, 273-75, 347-50.

Andrews, Evan. "11 Things You May Not Know About Marco Polo." History, Updated 31 Aug 2018.

Chojnacki, Stanley. “Patrician Women in Early Renaissance Venice.” Studies in the Renaissance, vol. 21, 1974, pp. 176–203. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2857154.

"Cibao Valley." Britannica.

Clarke, Paula C. “The Business of Prostitution in Early Renaissance Venice.” Renaissance Quarterly, vol. 68, no. 2, 2015, pp. 419–64. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.1086/682434.

Crowley, Roger. "The Genius of Venice." Smithsonian Magazine, 15 Oct 2015.

Davidson, Alan. Tom Jaine, ed. The Oxford Companion to Food, 3rd Ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. p. 236, 612-13, 767-8.

de Rachewiltz, Igor. "F. Wood's Did Marco Polo Go To China? : A Critical Appraisal by I. de Rachewiltz." The Australian National University, Division of Pacific And Asian History.

"Description of the Island of Chipangu, and the Great Kaan's Despatch of a Host Against It." The Travels of Marco Polo, Book 3, Chapter 2 (Wikisource). Translated by Henry Yule.

Figueroa, William. "Sino-Persian Exchange Along the Silk Road." Scottish Centre for Global History, University of Dundee. 6 April 2021.

Herriott, J. Homer. “Folklore from Marco Polo: Japan.” California Folklore Quarterly, vol. 4, no. 4, 1945, pp. 398–403. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1495625.

"History of the Major Trade Routes - Summary on a Map." Youtube, uploaded by Geo History, 27 Sep 2021.

"History of Venice: Rise to Glory." Youtube, uploaded by Epic History TV. 14 Dec, 2018.

Markham, Clements R., translator. The Journal of Christopher Columbus (During His First Voyage, 1492-93) and Documents Relating to the Voyages of John Cabot and Gaspar Corte Real.

Man, John. Kublai Khan: The Mongol King who Remade China. Great Britain: Bantam Press, 2006. p. 364, 368

McKee, Sally. “Women under Venetian Colonial Rule in the Early Renaissance: Observations on Their Economic Activities.” Renaissance Quarterly, vol. 51, no. 1, 1998, pp. 34–67. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2901662.

National Geographic Society. "The Silk Road." National Geographic Resource Library. Updated 26 July 2019.

Satya, Laxman D. "Debunking the Myth." Education about Asia, vol. 4, no. 3, Winter 1999, pp. 48-51.

"Silk Roads: the Routes Network of Chang'an-Tianshan Corridor." UNESCO World Heritage Convention.

Szcześniak, B. “Recent Studies on Marco Polo in Japan.” Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 76, no. 4, 1956, pp. 228–29. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/596149.

Turner, Jack. "The Spice That Built Venice." Smithsonian Magazine, 2 Nov 2015.

"Venice." UNESCO Silk Roads Programme.

"Venice in the 14th Century." Britannica.

Waugh, Daniel C. "Richthofen’s ‘Silk Roads’: Toward the Archaeology of a Concept." 2010.

"Western contact with China began long before Marco Polo, experts say." BBC News, 12 Oct 2016.

Williams, R. John. “A Marvelous Work and a Possession: Book of Mormon Historicity as Postcolónialism.” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, vol. 38, no. 4, 2005, pp. 37–55. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/45227339.