RENDERED 10: Pumpkins

Pumpkins in folklore: How a food becomes symbolic, and how symbols change

Welcome back to RENDERED. This month, my interests in food history, folklore and art come together to look at the history of the pumpkin.

I'm fresh back from a visit to the United States; more specifically, to my home region, New England (paid subscribers got to listen to the history of lobster rolls in a special edition of TIDBITS, recorded live in my mother's basement). One evocative aspect of the fall season in New England is the backdrop: corn, pumpkins, tones of changing leaves.

At one point, driving down the highway in Vermont, there was a precise moment where the clouds opened up and the sun hit those leaves perfectly: something deep inside me was comforted, energized, even electrified. The scene was nearly hypnotic.

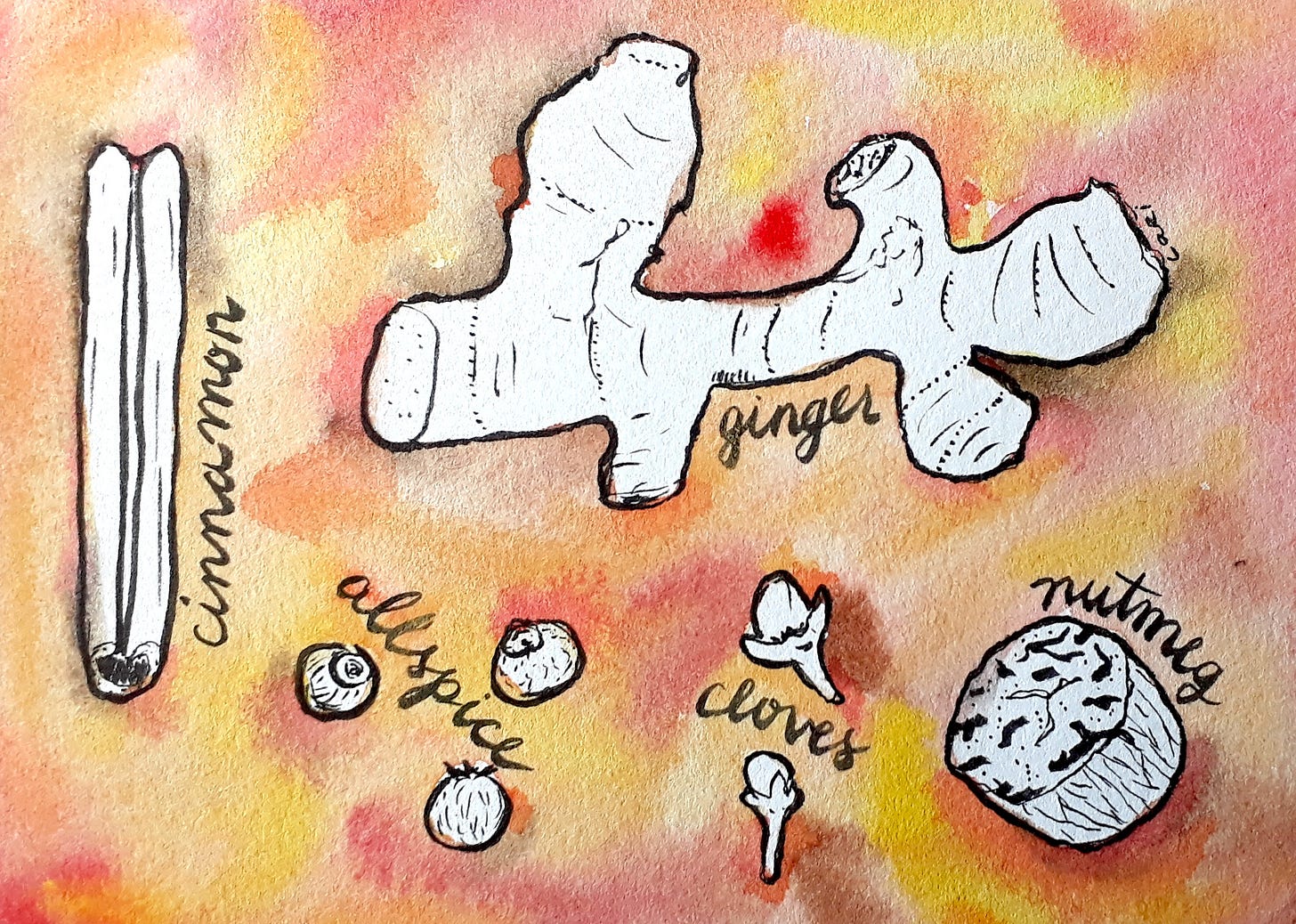

Pumpkins are also part of my visual language: they belong to a color palette that makes perfect sense to me. Both as decoration and culinary ingredient, pumpkins are everywhere: on display with stalks of corn, carved into jack o'lanterns, made into pie, latté flavoring... That scenery, those colors, that visual language all tap into something deeply formative. There is an old familiarity with it all, this environment that feels like "coming home."

Driving past my university, I thought back to my years studying Comparative Literature, the perfect major for someone who wants to tie their different interests together. Graphic novels and Japanese studies came together with Children's Literature and Education, and I arrived at folklore. It became of such interest that I applied for a Master's in the discipline. (I didn't end up going down that path.)

Why folklore? It includes folktales (legends, myths, fables, fairy tales), which transmit lessons, values, and morals to children. It brings up questions that I find interesting: How do stories, spread through oral tradition, use symbolism and metaphor to transmit lessons? How does that symbolism branch out and touch other aspects of our collective consciousness?

In the article "Why Fairy Tales Matter: The Performative and the Transformative" by Professor Maria Tatar, there is transformative magic not only in stories themselves, but in us, the readers. Magical thinking is possible, in that world. We can imagine having more agency, which is an empowering possibility to present to a child.

This month, I'm combining my interests in folklore and food history. Let's look at pumpkins: not only their history, but their symbolism (and I'm not just talking about Halloween.)

What is folklore, and what's the difference from 'fairy tales'? According to this article, folktales are primarily passed down through oral tradition, meant to be for everyone, as there is usually a moral to be learned. Fairy tales feature magical scenarios, and were written for aristocratic audiences by a particular author, often with a happy ending. Cinderella by Charles Perrault is an example of a fairy tale.

Included in the family Cucurbitaceae are softer summer squashes (like zucchini), and thicker-skinned winter squashes. Pumpkins are just one variety of winter squash--others include acorn squash, kabocha (Japanese pumpkin), butternut squash, and spaghetti squash. They have been cultivated since around 5000 BCE (perhaps even 7000 BCE!), are all native to warmer regions of the Americas, and don't do well refrigerated. The pumpkin is one of the first cultivated foods in the entire Western Hemisphere. (Etymology fact: the word "squash" came to English via a Narragansett word for "eaten raw.")

The word "pumpkin" comes from French pompon, which comes from the Greek pepon, meaning "large melon." It's hard to define a "pumpkin" precisely, because the name can refer to any member of the winter squash family. They're embedded into many different folklore traditions.

In a Persian fable called "Rolling Pumpkin" (Kadu Qelqelezan), an old woman must pass through a dangerous forest filled with hungry animals to visit her daughter. She convinces the wild animals she meets along the way that she'll be back soon, leaving them waiting for her return to gobble her up. After she visits her daughter, the old woman hides inside a giant pumpkin for the trip back through the forest, and rolls on past the animals, making it home safe.

The pumpkin provides the woman safe passage, almost akin to Cinderella's transformed pumpkin carriage. The difference is that Charles Perrault wrote the pumpkin into his story, Cendrillon, in 1697, by which point the orange pumpkin from the Americas was already known. The pumpkin in the Persian story was likely a different ingredient, eventually becoming a pumpkin. One clue that tells us this is the language itself: "Kadu" in Persian can be used for "zucchini" as well as "pumpkin."

This type of renaming has been known to happen elsewhere. In creation stories from some traditions in India, China, and Southeast Asia, pumpkins also appear--sometimes to save humanity from a great flood, other times to symbolize fertility and the birth of humanity. But, if they use the word "pumpkin," do they refer to the round, orange vegetable? Nope. The pumpkins in those stories are likely Benincasa hispida, or winter melon/wax gourd, which is native to the region. After the voyages of Columbus, Curcurbita (our famous winter squashes) became more well-known worldwide.

This is an example of "marking reversal," where a non-indigenous object arrives and takes on more significance than a similar, indigenous object with a longer history, resulting in the New Guy taking on the name. The indigenous object is then renamed with a remix or derivative of its old name. Voilà, a transformation by way of symbolic language.

These stories predate the age of European colonization, and featured gourds (or other ingredients) that were native to their regions. A more homogenized mental picture associated with "pumpkin" came along with the post-Columbus world.

We change systems of meaning all the time. As long as people generally go along with it, they agree to the change just by engaging with it.

Of course, seeing as we're in October, aka. prime spooky season, I would be remiss not to look at the season of Halloween, with jack o' lanterns in our face all month.

Not to be confused with Día de Muertos, the tradition in Mexico (particularly Oaxaca) where one pays respects to their ancestors and departed loved ones--one element of an ofrenda is candied pumpkin. I found two videos (both in Spanish) on Youtube which show us how to make calabaza dulce: De mi Rancho a Tu Cocina and Recetas familiares de Olga.

Halloween today is associated with carving jack o' lanterns, costumes, and trick-or-treating (all considered to be children's activities, according to my European acquaintances).

But for those of you who may not know, these customs have their origins in an ancient Celtic holiday called Samhain (pronounced "SOW-in"), marking the New Year, the day by which the harvest was to be completed, and preparations made for the winter to come. It is a time when the division dissolves between our world and an otherworld, between the natural and supernatural, life and afterlife. A folk custom called mumming involves setting out food as an offering to lost/wandering spirits--this became offering food to those who mask themselves in the guise of those wandering spirits.

Samhain traditions were not documented on paper (12th century) until well after Christian missionaries had settled in (5th century). During this time, the church moved around the yearly timeline so that the Feast of All Saints would coincide with Samhain, and the Celtic figures were rebranded as evil. This brought a connotation of danger and malevolence to that which exists outside of our natural realm. All Hallows (from halwe, Middle English for "saint"), or All Saint's Day, is preceded by All Hallows Eve/Hallow Even/Hallowe'en, when the supernatural activity is at its peak.

Why the jack o' lantern? It comes from an Irish fable of the blacksmith named Stingy Jack, a trickster figure who both outwitted the devil and was barred from heaven. Jack perpetually wanders the world with the vegetable he was eating, filled with red-hot coals to light his way. People began carving faces into vegetables like turnips, lighting them with candles to scare wandering spirits away.

Irish immigrants to the US brought along this tradition, meshing it with the pumpkins that were widely available, thus bringing us the iconic, spooky jack o' lantern. Like with the folktales above, the tradition survived, adopting a new object to stand in so that tradition could continue.

On the one hand, it can be comforting when one specific image (here, the symbol of the pumpkin) is so widely known and associated with sustenance, protection, and autumn traditions.

However, that homogeneity comes at a price: the larger symbol of the pumpkin has stepped in to eclipse other symbols from localized folkloric traditions. And let's face it: the pumpkin, as many think of it today, is a vegetable that wouldn't be known if it weren't for European colonization, which introduced it to the world.

I return to the question of symbols: they live in our minds, both personal and collective. How often do we get to choose our symbols for ourselves, and how much do we receive from our enculturation? If we question symbols, we question norms and the systems that created them. How does engaging with certain symbols as "normal" inform our worldview? And how can we, as individuals, comment upon it?

This brings me to the transformative power of art. I don't know about you, but if I think about art and pumpkins, I think of Yayoi Kusama.

Artist Yayoi Kusama has famously shown affinity for pumpkins in her immersive, hallucinatory art that features vast fields of polka dots (or, "infinity nets"). She shares her experience of living in a polka-dot universe with us, the viewers. Pumpkins, as described by the artist, are warm, humorous, human-like. It is with this knowledge that you experience her work: you are just an observer, a speck engulfed in the massive infinitude that she creates; through this medium, you accept her unique presentation of pumpkins, the symbolism that she has assigned to them.

Storytelling is symbolic and powerful--transformative, even. Art is just one way of telling a story, addressing symbols that have become entrenched in the collective mind: you use them, rework them, question them, or outright reject them. These are ways for us to engage in magical thinking. I leave you with this question: How does your magical thinking transform your world?

Thanks very much for reading. If you enjoyed this month's piece, please like/comment/share to help this newsletter grow.

If you would like to support my efforts financially, you may consider becoming a Paid Subscriber. Paid subscribers receive bonus content like original art and one bonus narrated essay per month, which I call TIDBITS. I also accept one-off donations via my website.

To follow my art practice in the meantime, follow me on Instagram or my website.

Be well, take care of your heart, and I'll see you next month.

Bibliography

Davidson, Alan. Tom Jaine, ed. The Oxford Companion to Food. 3rd Ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. p. 235, 659.

Grannan, Cydney. "Why Do We Carve Pumpkins at Halloween?" Britannica.com.

Marr, Kendrick L., and Xia Yong Mei. “Benincasa Hispida (Cucurbitaceae) the ‘Pumpkin’ of Asian Creation Stories?” Economic Botany, vol. 55, no. 4, New York Botanical Garden Press, 2001, pp. 575–77, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4256492.

McGee, Harold. On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. New York: Scribner, 2004. p. 333-4.

McGinnis, Esther. "Dakota Gardener: The Rich History of Jack-o'-lanterns and Pumpkins." North Dakota State University, 13 October 2020.

Santino, Jack. “Halloween in America: Contemporary Customs and Performances.” Western Folklore, vol. 42, no. 1, Western States Folklore Society, 1983, pp. 1–20, https://doi.org/10.2307/1499461.

Tatar, Maria. “Why Fairy Tales Matter: The Performative and the Transformative.” Western Folklore, vol. 69, no. 1, Western States Folklore Society, 2010, pp. 55–64, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25735284.

👍🏻🎃

💛